THE LONG ROAD TO SELF-DISCOVERY

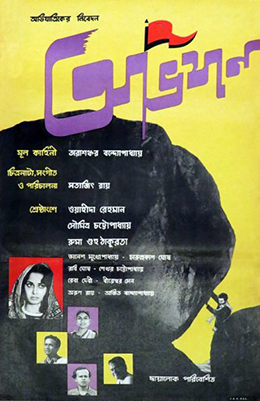

One of the few films by Satyajit Ray to feature a non-Bengali protagonist, Abhijan is also one of the most overlooked in his oeuvre. He rarely made more mainstream films than this, with car chases and rough-and-tumble fights. Soumitra Chatterjee plays against his type in this one, and the presence of Waheeda Rehman (in a role similar to the one she played in Pyasa a few years earlier) signalled a shift towards pleasing more popular demands.

But it will be foolish of us to think this film is anything like other mainstream cinema. It is chock-full of deep characters and symbolism, and is a treat just to watch Chatterjee perform perhaps his most atypical role as the drinking, swearing, whoring, law-breaking, taxi-driver.

Rejection As The Root Of Discontent

The first thing we get to know about Narsingh is that his wife left him for another man. As he drinks his way through to numbness, we can see the tell-tale signs of a man set on the path of self-destruction. This rejection, by the one closest to him, will colour the way he sees every other human interaction he had, has, or will have.

Rejection has a way to tightly clutch our heart and brain. It can drain every bit of trust we have, and replace it with the poison of suspicion and even the cold blade of paranoia. Like Karuna in Kapurush, Narsingh is a man who will struggle to put his faith in anyone again. He is convinced that people are out to get him, and in an unfair and unfeeling world this can often be the truth.

Following his wife’s departure, Narsingh feels singled out by the authorities for breaking the law when others do so with impunity, or so he feels. Even when he moves to another town, he is faced with opposition from the local taxi-drivers there who try and make his life miserable, even to the extent of physically harming him. How is this man supposed to feel anybody is on his side when clearly no one will leave him in peace?

Rejection can feel like the only means of self-preservation. When we are repeatedly made to feel unwanted, our bruised ego then starts to reject others pre-emptively. Don’t trust, because then you will be broken-hearted, is the logic behind it. This is the reason why so many people maintain a detached or withdrawn posture. This is why people stop believing in true love, friendship, and even basic goodness.

There may be no such thing as a free lunch, but why should I always be the one paying, eh?

To add to it all, Narsingh’s identity is too tightly entwined with his caste association. As a Rajput, member of a warrior caste, he is doubly shaken by rejection because it makes him feel like a let-down to his heritage. He is shaming his ancestors by allowing so many people take advantage of him. It’s better that he should die in battle than be shamed by such nobodies. Better to die trying to overtake an obstructive car than to meekly follow along under its shadow.

Such feelings of being cornered is also why he is quick to align himself with Sukharam, the businessman who offers him the chance to start over as a partner in his smuggling business. This shows the vulnerability of Narsingh – the man with the tough exterior is desperate to be acknowledged by someone, anyone. To be praised by this dubious man fills a deep need for validation in him. His inner thought would be along these lines: “Yes, I am important. Yes, people value me. Yes, I deserve respect. No, everyone cannot walk all over me.”

It is possible to sympathise with his brusque and even criminal behaviour when one looks at it this way, and that’s what Ray would expect of his viewers. Look at why this man is hurting and wonder if we have ever felt this way, and made people feel this way. Narsingh is a man trapped in a cage of rage and the only way to release him is by making him feel understood.

Self-Medicating With Anger And Isolation

There was a popular trope in mid-twentieth century literature – the angry young man. Most Indian audiences would be familiar with this concept in relation to a number of Salim-Javed-Bachchan films, but the origin of this was in British theatre.

The first character for whom this term was used was Jimmy Porter (from John Osborne’s play Look Back In Anger). Unlike the Bachchan hero, Jimmy Porter was no uniformed crusader of the law, but instead an utterly dislikeable and belligerent man. And yet the point of the play was not to give us a figure to hate, but rather to understand how someone can feel so trapped in by obstacles to self-actualisation that hatred becomes the primary face of their entire personality.

This is not the anger of intolerance, bigotry, or bullying. This is the anger of having your back to the wall and trying to punch your way through life. Narsingh has become addicted to his anger as a way of negotiating with life. He cannot abide the slightest suggestion or criticism, he cannot slow down his car for safety, he cannot even accept the concern of a few people around him. He is a rebel without a cause.

That is the deficit that finally threatens to do him in. His assistant Rama is trying to be his friend, Gulabi is trying to be his life partner, Neeli and her brother Joseph are trying to be his counsels – Narsingh’s life could actually be rich in friendship. But alas, he has closed himself off so tightly that he misses these obvious supports. He goes so far as to abuse the woman who is trying to give him love just so he can prove to himself that he is no victim to human emotions. He has become a Scrooge.

Being squeezed out by the world is a very real problem. But there are still some people, themselves victims of injustice, who can empathise and offer you a helping hand. If one’s anger blinds one to these escape routes, it is only then that one is truly doomed, not sooner.

Such anger is suicidal. It makes the chances of achieving balance and respect impossible because its scale grows so impetuously. There are impossible standards set which almost conspire to keep any reasonable chances of happiness away. It rejects any thought that a better future is possible because to admit that would mean we can make choices. But to be able to make those choices we will have to become flesh again, and not stone, and that’s a truly frightening thought in a cold uncaring world.

Identity As A Journey

While the first journey Narsingh undertakes is from Town A to Town B, the second and more meaningful one will be one without a destination, just a direction. When he finally decides to leave the second town and his role in an illicit business, he takes Rabi and Gulabi with him. Narsingh has just embarked on a journey towards uncovering his identity.

Just before his escape Narsingh had been surrounded by the boulders of the Mama-Bhagne rock formations. While there he realised two things – one, that he cared what his friends thought of him, and following from that, two, that he wasn’t a man of stone like he wanted to believe.

All through the movie, he had tried to convince himself that he was a lone wolf, a man who didn’t care about anyone but himself. But he thought this despite evidence to the contrary. He cared about many people – he lost his heart to Neeli and then had it broken, he didn’t like that he fell in the estimation of his friend Rama, and he couldn’t abandon Gulabi to her miserable fate even if it meant learning to trust women again.

Narsingh came to realise that his identity was not just his Rajput heritage, his job as a taxi-driver, or his eternally scowling eyes. Identity is an evolving thing, a sum total of our experiences and our principles. Each day brings new experiences so how can identity be locked in stone?

Though he may have tried to put a seal on it, eventually Narsingh had to acknowledge he cared about other people, including those he met only recently. They also made him feel good about himself, something he never expected. To remain stubbornly boxed in by only a few early indications of who we are meant to be is to sin against oneself. To evolve and uncover our own identity is one of the blessings of life itself.

Our identity is not something we can consciously determine. We can only try to examine it, accept it, and where it causes pain to ourselves or others, change it. It took some rather desperate events in Narsingh’s life to realise this, but then to see him finally learn to love himself for the resilient, tender, caring person he is – that is the really reward of the journey.