DIRECTOR’S CUT

If Satyajit Ray made twenty-seven feature films and two short films for us (not counting the documentaries), then these last two of his films were just for him. Out of his thirty-one fiction films, only eight were his own stories, and of those eight these were clearly his most personal ones.

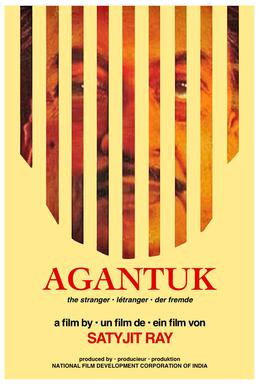

These numbers are just to remind us why these two films, namely Sakha Prosakha and Agantuk, stand apart from the rest of his filmography as being more memoir than fiction, and also why for these two essays I’ve broken my own general rule of not approaching his films biographically. Especially for Agantuk, because one can see the character of Manmohan often completely overlapping with Ray himself, and never more explicitly than when Ray’s voice, literally, sings through Manmohan’s lips.

Approaching The Bench

Even though Agantuk is about an unexpected guest entering the home of a small family, who may or may not be a distant relative, what it really is is a courtroom drama. By using the suspicion aroused in the minds of a few about the veracity of this man’s identity, Ray creates many occasions to have the guest, Manmohan, treated like an accused in the dock.

The range of concern runs from protective (Sudhindra wants to make sure his family and their possessions cannot be swindled), to curiosity (an actor friend and his wife treat it like an exciting mystery), and hostility (a lawyer friend who cannot hide his contempt for such criminal behaviour). So many emotions are raised by this visitor that he spends most of the movie defending himself.

By placing his character in that situation, Ray too seems to be defending himself through him. At the end of a long career he seems to be giving his last interview.

Especially when butting heads with the hostile lawyer, Manmohan talks about his views on religion, on sexual politics, on civilization, and on life lived as a man on the move. In the movie most of these encounters fail to move the audience, but then again it’s not about us. It is likely that the many socially-conscious, even boundary-pushing, films he made would have invited the ire of many conservative critics. This could have been the director’s response to them, not us. He may have shown women adapting to a changing world and exploring spaces that were never open to them before, and this may have made him a target of said conservatives.

Ray was not a perfect man, as his last two films reveal. But he was brutally honest. His films would have made his audience uncomfortable, something not many film-makers, especially in India, can risk. He worked with known and unknown actors, he never did the same thing twice, and for all this he knew he was always taking chances.

But the great arc of his career was always about using his cinema to nurture a more aware and responsible audience, something he hoped the power of cinema could do. In his previous film, it felt like he considered that project to be a failure, bemoaning the worsening ways of the world. In this film, the bitterness continues as he claps back at those who may accuse him of compromising his bhadralok civilities. Manmohan keeps expressing his love and respect for tribal communities and calling modern civilization, or indeed all civilization, a heap of contradictions.

Whether it is a sign of wanting a slower pace of life in his old age, or bitterness brought on by the evolution of mainstream cinema, Ray also seems to want to cast off all signs of artifice, including even in his film. Manmohan says he admired a cave painting of Altamira so much as a youngster that he gave up drawing because he felt he could never make what those palaeolithic humans had drawn. One of the final things Ray shows us in this film is a dance by the Santhal tribe, recording it almost like a documentary, to be preserved and admired as the greatness of our collective history. He seems to favour moving away from the dazzle of films and return to art that is much more intimate, much more personal, and only represents an individual’s humanity and not anything industrial.

Overall this film is a painful goodbye, even though it has a warm ending. One gets a sense that Manmohan’s character is meant to show how ill-at-ease Ray may have been at the treatment given to him. Where on the one hand he had lived an exemplary and enviable life, on the other he may have been unable to do what he wanted to because it was in the nature of ‘civilised’ humans to question his intentions. Even despite that he wanted to reward those who stood by him, his loyal audience, for whom he wanted to bring the message of purity and simplicity that have been etched since time immemorial, not on cinema halls but on painted cave walls.

A Person’s Provenance

If that was his opinion on art, what did Ray want to convey about the human being behind the art? In the story, the arrival of an unexpected guest in the house throws up a very critical question – how does one know if this person is who he claims to be? Manmohan’s niece is delighted to get to see him after nearly a thirty-five year absence, while her husband Sudhindra is suspicious. He worries that such a long gap, and the fact that none of Manmohan’s contemporaries are alive or in sound mind, leaves them vulnerable to conmen.

Just how does one confirm identity? At the very basic level there are documents, like a passport, which are acceptable for all official purposes. However, these don’t change with time and offer nothing but a name, date of birth, and birthmarks. Can a family accept this much as proof?

What then is a person’s inalienable personality? Maybe their memories. The knowledge of facts that nobody other than the one asking the question and the one answering will know. But when people from your past have died, and you are the last one standing, are you no longer the person from those memories?

The last, and frankly most unverifiable method, is what Ray refers to as family blood. This doesn’t signal any kind of racial theory, but the unique set of values and characteristics that a family defines itself by and inculcates in each generation. This can be things like a shared love of a certain kind of food, or even the manner of eating. It can be a predilection for a kind of fiction, or music, or even a manner of speech. Maybe people have similar tempers, or sense of joie de vivre. Then one can look at matters of taste, perhaps there is a similar sense of fashion or interior design. For Manmohan, these are the real bonds that cannot be broken even after a lifetime of travel and not meeting. Like a mother will always recognise her child, any strongly bonded family will be able to recognise each other, he seems to say.

For him, family connects almost instinctively, like animals that recognise each other’s scent. It is not contained in a passport or even in a person’s history. Just by asking for an account of a person’s travel or work history, the person cannot be known. True knowledge of a person comes by spending time with them, getting to know them, and above all, by starting from a place of trust.

Identity, then, is a combination of one’s formative experiences (blood), their memories, and the sum total of their life experiences. It is not their name, age, skin colour, sex, birth marks, or curriculum vitae.

Unfortunately, like for the younger generation in Sakha Prosakha, these are values that are difficult to rely upon because they are so very ephemeral. The cost of misplaced trust can be quite catastrophic, so starting from a place of trust has become more and more impractical. But instead of thinking of this as advice we are probably better off if we think of this as Ray’s yearning for a time when giving a stranger shelter and enjoying their company was a way to enrich one’s own life. While this notion of ‘simpler times’ has always been a little disconnected from reality, it is also true that that is how things ought to be.

One way we could start being able to trust people would be if we had lesser to lose. By collecting so many valuables in our overcrowded homes we have made it impossible to let anyone in without verification. So the embellishment of our personal spaces has cost us in terms of experiences. One’s home can no longer be open to a stranger.

Wanderlust For Life

In Manmohan’s life there are no such inhibitions. Not only will he be the visitor more often than the host, his state of perpetual motion means he is not a man attached to any place or possessions (except perhaps his suitcase). In his own words, he has always been possessed by wanderlust, and that has taken him on travels to four continents (soon to be five).

Having studied anthropology, he was ready to fulfil his desire to travel to remote places and encounter people from diverse backgrounds. The lasting impressions were always left by tribal and forest-dwellers. In them Manmohan found the purest form of human civilization, where there are no man-made divisions, no demeaning hierarchy, and a form of sweetness that nourishes the soul. He is proud to have lived among them, eaten what they eat, and enjoyed their music.

[Once again modern viewers may find themselves conflicted about accepting what Ray has to say. There is a peril in romanticising indigenous cultures, as this film is at risk of doing, because then the anthropologist’s opinion may get prejudiced. After all, sometimes we may praise someone but then make that person serve us because, we argue, that is in their helpful nature. The depiction of tribal folk, or domestic workers, in this film (or even in others like Aranyer Din Ratri, and Kanchenjunga) can feel a little self-serving. I am certain this was not intentional, but even so it requires some correction in our minds. It must be remembered that Ray was well ahead of his time, but not ahead of all time.]

Even after returning to his birthplace he knows he will only be passing through. The one thing Manmohan will never be is a kupamanduk, or a frog in a well. For him life becomes stale in one place and his spirit and imagination need to constantly roam. And somewhere we feel this is also what Ray thinks about the journey of one’s soul.

What frightens us most about the end of life is whether there are any more journeys after that or if it’s all over. In most cultures there is an afterlife, and for many Indians after life is about rebirth. One’s soul leaves one body and then inhabits another, not necessarily human. In a way this too is wanderlust, the need to shed off bodies when they have run their course and move on to the other one. Ray at this stage in his life may have been prepared and even eager for the next destination. When his grand-nephew asks if Manmohan will never return to meet them again, Manmohan replies that next time it should be the boy who comes to visit the old man, maybe in a different continent or a maybe in a different life. Even in different lives they will be drawn to each other.

But his most personal task when he is in one place, especially when his grand-nephew is around, is to impart a sense of wonder about the world. A world traveller has a palette of manifold more colours than settled people. As such, Manmohan is best placed to make the child see things he hasn’t seen before, and invest something magical back into the world he lives in. That’s what every good film-maker also desires, to open our eyes to new sights and feelings, to surprise us and make us twitch in our seats, to make us think and continue the journey long after the film is over. A hundred years after his birth, and thirty years after his death, the many journeys of Ray’s films are far from over.