ACCEPTANCE AS THE FINAL RESORT

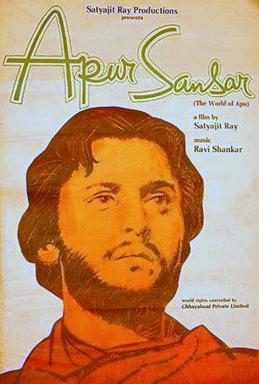

Is it possible to have a song on your lips when the world keeps attempting to steal your voice? Apurba experiences his life’s highest high and lowest low in this film and manages it all without any of the grand gestures cinema is all too fond of. Along with the adult Apu, cinema-goers are also introduced to Soumitra Chatterjee (who plays the role) – the birth of a colossus of world cinema, and one of the most charismatic actors to ever come out of India. It is also the debut of Sharmila Tagore, another pathbreaking actor who would go on to star in many of Satyajit Ray’s films, as well as popular Hindi films. This film is the gift that keeps on giving, and a splendid conclusion to the trilogy.

The Support Structures Of Reform

Like the great nineteenth century European masters of literature (whom Ray admired), Bibhutibhushan Bandhyopadhyay’s story is, at its heart, a plea for social reform. Each defining stage in the life of Apu is one where he has to choose between the traditional and the modern, and the traditional is almost certainly the path to misfortune. The only solace it provides is a support structure in the form of near and distant relatives who offer some much-needed help from time-to-time.

Is it not possible to make life-affirming decisions, move away from the more harmful effects of the past, while also maintaining a warm and nourishing social structure? That’s what we are asked to ponder in this final instalment of the Apu Trilogy.

We encounter a very different Apu at the start of the film – one who is confident, intelligent, full of joie de vivre. Quite frankly, he’s happier than anybody has ever been in the story thus far. What hasn’t changed, though, is that he is still short of money. While he graduated to living with electricity in the last film, he still doesn’t have the means to make ends meet, including paying his rent or electricity bills. Even more tragically, he has to drop out of college before completing his honours degree because he cannot afford the fees.

Yet we feel he is immeasurably happy and there are two reasons for this. The first sounds cold-hearted, but he no longer has anybody to worry about. Having lost his family, left home, and resettled in the city he will never have to worry about anybody’s happiness apart from his own. Moreover, in cities people don’t suffer hunger like they might in the villages, and he is not homeless either. Having seen the deprivation he has, life can feel quite rosy even with so little.

The second reason is altogether different – he has a true friend. Pulu is a welcome member of his life, one who forms a break from the past. Apu is the only person from his family who has been shown to have any friends at all. By moving away from home for his studies, he formed an alternate support structure, one which didn’t put any burdens on him and instead offered a much-needed source of cheer. And Pulu offers him much more than fun and games, he offers professional help, financial help, advice, encouragement, and never does he ask for anything in return except friendship (at least not until the episode of the wedding).

This becomes an incredible foundation for Apu, allowing him to dream and spread his wings. He even describes the novel he is working on to Pulu, which doubles up as a speech on how he sees himself – a person who has been deprived of everything and yet wants to be ambitious and happy. Aparajito!

Some Heart In The Mind, Some Mind In The Heart

And if only he had stayed true to his path he could have avoided the one final, and possibly greatest, disaster of his life.

When Aparna’s intended marriage goes awry, Apu is asked by Pulu to step in and marry her. It is an uncharacteristic request from Pulu, and even more uncharacteristic of Apu to accept even though he acknowledges the risks. He doesn’t have the wherewithal to support a wife and any future children. Yet, it is the pressure of blind faith (that if the girl doesn’t get married within the window of auspicious time, never mind to whom, she will remain unmarried forever, which is a fate tantamount to death) that forces his decision, and not love or rationality. Additionally, there would be a not-insignificant amount of guilt on Apu if he were to reject the pleas of his only friend.

Not only does he condemn himself to a life of financial pressure, he condemns his bride to poverty and deprivation that she has never had to face. Moreover, when Aparna dies during childbirth, one also questions the wisdom of child-marriages and the effect it has on frail bodies of underage women. Though these were commonly accepted practices across the world, someone like Apu should have known better than to impregnate his barely fifteen-year-old bride. Alas, misfortune finds its way back to Apu once again.

What is the value of such struggle, such learning, such independence, if we do not apply it to life’s toughest decisions? The road to hell, after all, is paved with good intentions. And instead of reacquainting himself with his own values, Apu makes another bad decision after the first when he abandons his child. Once again, a disproportionately emotional response to his dilemma thrusts Apu into abandoning the entire plan of life he had built.

He leaves Calcutta, disappears into a string of jobs in a string of small towns, throws away his manuscript, all in a misguided effort to try and outrun his pain. But how could that even be possible? He has instead run headlong into it by depriving himself not just of his son, but also his writing talent, and a chance to undo all the mistakes of the past.

Of course, one cannot be unduly harsh on the poor soul, after all life is very often beyond recovery for many people. The myths of “take it in your stride”, “don’t give up”, “you just need to try harder to be happy”, are all venal and impotent words of advice to one whose every attempt at readjusting has been thwarted. Apu has tried and tried damn hard to make a new life for himself, so I will never blame him for reacting the way he does to his beloved wife’s death.

And yet, there is nobody else who can do anything for you at your lowest points except you, yourself. We should be so lucky as to have even one friend like Pulu, who tracks down his friend in the middle of nowhere, to convince him to take back the guardianship of his son and re-attempt life. But even with such a benefactor, the strength needed to lift oneself off the floor is still one’s own.

And this is where Apu goes from being a fighter to being truly heroic. He does pick himself up, he does brush off the pain, and he accepts what he has to do. And despite the interference from his father-in-law (the source of all misery in this film) he is tender with Kajal, his son. Apu knows love and how to give it. He knows he has to win his son’s heart and not commandeer it. Apu is special, he is strong. He is unconquerable.

Good News, Bad News, Who Knows

After the relentless assault of death and misery through all three films, none of us can feel doubtlessly positive when the film ends. It is probably on everybody’s mind that even after the last scene fades to black, we can hardly be sure that Kajal won’t suffer some mysterious illness, or Apu won’t die and leaves his son an orphan. It is, after all, that kind of story.

Which of us really knows how far we can trust life. Misery will almost always hit us harder than happiness. Anything we have is something we can lose. So then why try?

If that’s how we feel when the movie ends, then we are much weaker than Apu.

Apu, in many ways, is a stoical hero. He belongs to the school of thought that learns not to attach too much value to the highs or lows, and instead embrace a kind of middle path. To be excessively happy when you have seen what life can do is an act of pure foolishness. And to be excessively sad is an act of foolishness as well. What looks like a fleeting moment of happiness, surrounded by clouds of gloom, is a lesson to live in the moment. Nothing more, nothing less.

I am not pretending that I am capable of that myself. But I hope to be some day.

And that’s what we need to take away from this film. Be a little more Apu every day. And whenever you find yourself in bad times ask yourself, “What would Apu do?”