WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS

A holiday brings the opportunity to disconnect and recharge while away from any kind of home rule. It promises both a productive and a dissolute period, where doing nothing is considered a very serious activity. The objective, no matter who you are, is to get away from work and all drudgery. If you’re an employee this means no office, if you’re a home maker this means no chores, if you’re a child this mean no studies.

In this simple fact is concealed the truth that there is some part of our self and psyche that needs to break away and act in a manner it is not allowed to. The Id comes out from behind the super-ego. We wouldn’t need holidays if our authentic selves were exactly what we are when working.

A holiday can also be an act of escape, a way of hiding ourselves from some unpleasant encounter. Maybe we don’t want to be in the same city when a former lover is getting married to someone else. Or someone is out looking for you to cause you physical harm. It becomes a way to be on the run without actually being a fugitive of some sort.

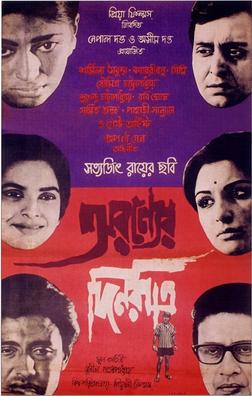

The group of four friends who go on a holiday in Aranyer Din Ratri have a mix of these reasons. They want to act out, escape rejection, eschew responsibility. It’s a journey into the wilderness, unstructured in a way to specifically avoid any responsibilities. The literal journey also turns metaphorical as each one reveals more of their authentic nature than they may have intended. Four friends, four days and four unravelling spools of thread under cover of the forest’s canopy.

Male Identity

Would it be too outrageous if I called this the bhadralok version of a boys’ road trip? All the men are in their twenties (based on circumstantial evidence in the story) and three of them (namely Ashim, Hari, and Shekhar) have the unbridled energy of youth as well. The fourth (Sanjoy) is quieter than the others. Each have their own reasons for this trip, but what each one needs is the companionship.

It is obvious how close they all are and one can safely assume their friendship goes back years. The fact that each of them has a different job than the other means they aren’t work colleagues. Therefore, their words don’t need to be measured, their behaviour doesn’t have to be restrained in each other’s company. There is nothing to hide here.

Ashim is a man of sophistication, at ease in high society parties and debonair in his presentation. He is the man-in-charge, a natural leader, and used to giving orders effortlessly. He is also the smoothest when charming women. A lot of this we can gleam from just a momentary flashback showing him at a party. He wants to assume his natural ‘alpha’ position, unlike how he has to be ‘beta’ at work. He needs to act pushy towards others for a change.

Hari is the athlete. A man of brawn and emotion, both of which are well-channelised in the sporting arena. He also likes to pretend women are objects for him and that he doesn’t like to dwell on them for too long. He is prone to flights of anger. In truth, we are shown he was left by his lover and cannot gather the courage to move on from this rejection. He is a sportsman who cannot abide a loss.

Shekhar is the class clown. He trades barbs with the others, and doesn’t flinch when made fun off. He is untroubled by the fact that he is unemployed and likes his freedom. The one vice he has is gambling, but even that is not something he is bothered by as he seems to be good at landing on his feet.

Sanjoy is the mild-mannered one. Quiet and observant. He is a labour relations officer in a factory and is torn between serving his superiors and serving the labour. He is a man who wants to do the right thing but is powerless to do so. To escape the tough choices he has to make at work he has come on this trip.

Thus, all but Shekhar have come with an agenda which is to be different from their usual city selves. In that order then they are journeying to a more pre-civilisational place to find their pre-domesticated selves. Where they don’t feel powerless, where they aren’t told what to do, where they can follow their hearts freely.

Ashim looks set to create trouble for underlings right from the start. This is his way of regaining the sense of primal manhood that he loses from time-to-time. By bullying the guest-house keeper he asserts his superiority. And yet merely being spotted by some women while bathing in his underwear emasculates him. It is a fragile sense of control that is easily shattered. A man of such effortless power, as he likes to think he is, should not wince at being seen deshabille.

Hari too is not a man of inner strength. He cannot take rejection by his lover and tries to use physical force to subdue her, because it is the only force he has. There isn’t much he can do to stop her from leaving him, and more importantly he doesn’t have anything that can make her want to stay. Like any athlete he has to wonder what happens to him when his bodily strength will inevitably start to fade. Can he still see himself as a man?

Sanjoy knows he shouldn’t follow the orders from his superiors but doesn’t have the will to back it up. He is a slave to his job and needs to see if he has the confidence to walk away from it. But is it manly to walk away from a righteous fight? Even later, when a woman he has been admiring offers his some physical comfort, he cannot act. He can neither accept her offer nor walk away.

Shekhar is the only one who seems comfortable in his skin. He is indolent, doesn’t like if his clothes get messed up, doesn’t like to work for money and gambles for it instead. He is not an admirable person, and yet neither is he someone who feels the need to pretend to be otherwise than he is. There is a crudeness about him which is also honest.

All four friends need validation from each other which is why they choose to take such a trip together. There is a sense of trust that they will not question or supress each other in the way others now do to them. Old friends can be a source of comfort in times of change, and they can take you back to the best days of one’s life. As such they are an escape from reality, and the trip is a form of hallucinatory experience.

These men want to act like the boys they once were, without consequences, and that’s just what they do.

I Hereby Claim This Land

In many works of literature and cinema, entering the forest is a passage to shedding civilization and morality. In a forest we have to be animals. One reverts to relying on weapons and teeth, and not words and diplomacy. Kill or be killed is the mantra and killing is not immoral or criminal. Famous examples like Heart of Darkness, Lord of the Flies, and Apocalypse Now, deal with the effects on the mind of explorers lost for years in the wilderness. Even some modern science-fiction tackles the impact of being adrift in space on human minds.

There is also a peculiar male tendency to treat exclusively male trips as a license to put on their worst behaviour. Many are the stories of groups of men on international flights getting drunk and misbehaving, or misbehaving on overnight trains. There are many-a-tale about wild nights in Las Vegas where no normal rules of life seem to apply. The popular saying sums it up beautifully, “Whatever happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas.” Indulge in your deepest, darkest, and your most degenerate desires, no one will find out. One can similarly say for this film, “Whatever happens in the aranya, stays in the aranya.” No respectable reputation is risked.

While none of the characters in this film are risking severe mental destabilisation in merely four days in a small forest town, they nonetheless treat their sojourn as a licence to act irresponsibly. Whether it is by bullying the attendant, by picking up a local to do their bidding in return for some money they throw at him (and later accuse him of stealing), or by trying to have some fun at the expense of some tribal women, they indulge in activities that would never be tolerated in the city. Even a light-hearted observation, that most of them didn’t pack shaving kits because they plan to reject grooming and let their beards grow in primal fashion, says something about their intent.

Overarchingly, there is an unmistakable colonial sentiment exhibited through them. Healthy and powerful outsiders cross the boundaries of their own land, come to an inhabited land with the intention of benefiting themselves at the locals’ expense. The local man they employ, Lakha, is a Caliban-like figure who is used and abused by them. Fittingly, it is this person who hunts out one of them in the thick of the forest and extracts his vengeance in a kind of uprising against the invader.

It is very clear that these four friends only care about their behaviour when people they consider to be their equals witness them. So getting drunk at the local bar is actively pursued, dancing drunk in the middle of the road at night is also part of the fun; but when they find out that some folks, also from the city, see them riotously drunk that it becomes a matter of great shame.

Their behaviour towards the tribal women is markedly different from their behaviour towards other city-women they meet. The tribal women are objects to be played with and laughed at. One among them, Duli, is especially seen as desirable and easy to victimise due to her alcoholic bent. Hari, nursing a heartbreak, treats conquering her as the perfect way to restore his own peace of mind and sets out to achieve this end.

Only Sanjoy, the labour relations officer, doesn’t take part in this systematic degradation and stays most silent. Of course, silence is not the same as taking a stand against injustice, which is the problem he is trying to get away from in the first place. In many ways it is even harder to protest the exploitative behaviour of old friends than it is to quit a job.

The other city-folk that the group chances upon is a family. It consists of an aged patriarch, his daughter, his widowed daughter-in-law and her child. Despite the men’s claims to wanting to spend wild nights on their own, they are instantly charmed into the company of others like them. The flimsiest of reasons keeps them close to this family – the promise of a hearty breakfast with eggs, something they could not cope without.

The women, both welcoming and generous, are contrasts of each other. Jaya, the widow, is vivacious and hospitable, glad to get the company of adults her own age. She is a woman deprived of the best parts of life since it is unbecoming for a widow to seek fun and enjoyment. Yet, she unabashedly takes advantage of the company to organise lunches and picnics and even a trip to a local fair. In her own way she is also using the forest to act out her hidden desires. This reaches its climax when she invites Sanjoy into her empty home and offers him intimacy. She changes into colourful, dressy clothes which she otherwise cannot do as a widow, and tries to seduce him. But her offer is neither accepted nor rejected, leaving her in tears. It seems a woman cannot get the same privileges as a man even in the forgiving shade of the forest.

The Edge Of The Forest

Aparna, on the other hand, is the only moderating force among these dissolute souls. She doesn’t seek to conquer the forest in the same way as the others, nor does she look for chances to impose her will on anyone. She doesn’t enjoy false pretences, something she sniffs on the men immediately. Ashim especially tries to woo her and is surprised to be rebuffed. He is mortified that she has seen him bathing and drunkenly dancing.

It matters very much to him what image she holds of him, not realising that the only times she’s been interested in him was when he was vulnerable. When the entire group plays a memory-based game, and she and Ashim are the last two standing, she allows him his victory even though she could have easily defeated him. Whether this is out of pity, grace, or a desire to avoid confrontation we cannot know. She does admit to him later that she could have beaten him, but probably doesn’t enjoy competitiveness the same way he does.

Aparna has faced multiple tragedies in her life, including the unnatural deaths of her mother and brother. Presumably such events have made her less tolerant of facetious behaviour than most others. With wisdom beyond her years she knows that Ashim needs to have his preconceptions challenged if he is to ever grow as a person.

But do they grow? The film ends as the journey ends and we are not left convinced that this trip has changed the four friends in any meaningful ways. We do not feel any of them have had epiphanies or found solutions to their problems. Even Ashim, who has been expertly diagnosed by Aparna, is likely to revert to the comfort of his usual ways and not use his chance encounter with this woman to change.

There was everything in this trip to make them better and stronger people upon their return. An entirely different view of life was presented to them but they choose to look away. By having their sights set on exploitation, they missed everything valuable. Modern humankind suffers from this myopia on a worldwide scale. They are bent on reckless consumptive behaviour and no voice from nature will ever penetrate their senses.