THE SEPARATION OF BODY AND SOUL

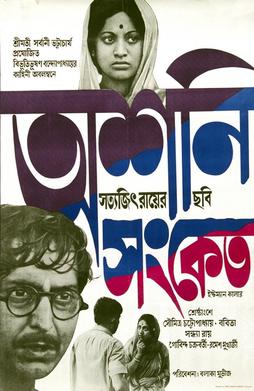

Although Ashani Sanket was Satyajit Ray’s second colour film, it is anything but a colourful film. After making many films about angst, alienation, and unemployment (with a couple of children’s films and a detective film along the way) Ray returned to the subject of rural poverty that he had dealt with in his early features, the Apu Trilogy. Unsurprisingly, all four of these films are based on the work of the same writer, Bibhutibhushan Bandhyopadhyay.

However, where the Apu Trilogy kept its focus on one family and their particular tragedies, Ashani Sanket dwells on an entire village and how every person is affected by a man-made famine. And, though the canvas is much bigger in this film, the deftness of the story is seen in how well each character is formed.

Wildfire Of Hunger

The presence of Soumitra Chatterjee at the centre of the film, playing the brahmin priest-cum-teacher Gangacharan, tempts us to treat this as a film about him. But this is not the case. Thanks to the great writing, Gangacharan is not the most important character but a conduit (or, point-of-view) for understanding the magnitude of suffering we are about to witness.

He and his wife are new to the village. They (and through them the audience) gets to know the other residents of the village one-by-one. Gangacharan’s high-caste status entitles him to certain privileges of life, such as gifts of freshly-caught fish, that allow him and his wife, Ananga, a comfortable life. Even though they don’t make much money, the kindness of the community keeps them well-fed and well-respected.

Soon enough, we know who is the richest man in the village, who is an untouchable, and what is everyone’s level of education or awareness about the outside world. In the midst of this we are also shown the sight of aeroplanes flying across the sky, which is a miracle for these people in the 1940s. Unknown to the villagers these aeroplanes are also harbingers of distress as they signal the approach of war, and also of hunger.

The historical event this film is based on is the siphoning off of food grains from India to Britain during the Second World War. This was done to support the fighting troops and ensuring stocks of food for British and Allied citizens, but it came at the enormous cost to the people of India, especially the region of Bengal.

Like the sight of scared animals fleeing a forest fire, the early warning signs come from other villages, from where hungry people start arriving in search of handouts or shared meals. Word starts to spread about rising costs, and even those who weren’t worried at first, start to weigh their future options.

Soon enough we see the impact of the war on the lives of the villagers. Scarcity of food leads to rising prices and a competition to acquire grains from the market. Suddenly, Gangacharan finds his supply of gifts has dried up, and he doesn’t have enough money to buy at prevailing market rates.

Even when he puts together enough money by selling his wife’s ornaments, it’s no good, as there is no willing seller. All-important money becomes useless as not even merchants want to part with what little they have for any price. They cannot eat money, as one merchant tells Gangacharan, so what good is it to sell even at high prices? Instead, he is offered a one-time meal at the merchant’s home, which he has to eat alone since his wife is not with him. A husband has to choose between eating alone or starving along with his wife.

The entire social structure breaks down as upper and lower castes, richer and poorer farmers, all find themselves faced with scarcity. No longer do people have time to show respect to Gangacharan, no longer can women of privilege stay protected in their house, no longer is trust worth more than a fistful of rice.

Each day the numbers of people arriving at Ananga and Gangacharan’s doorstep increases until they have to steel their hearts and start ignoring these walking zombies. One time that Ananga offers aid to a girl she once knew (although the offer is steeped in disgusting caste-consciousness) the girl is too weak with hunger to feed herself and dies, despite food being just inches away.

Even this village is just one domino in a collapsing pile. People from here also start to move on to other villages, amassing in numbers, until eventually there will be millions of hungry feet trudging their way towards Calcutta, only to face death even there.

What does this say about our ability to even comprehend, let alone solve, massive problems like hunger? It’s easy to treat these as problems solely linked to poverty or mismanagement that don’t affect the well-off. But that’s not just a selfish view, it is also short-sighted. Like a forest fire, hunger takes victims even outside its direct ambit. The smoke of hunger eventually reaches the well-stocked kitchens in cities, the fleeing animals can stampede to run you over, and the loss of life is irreparable.

Power Of An Empty Stomach

The way hunger affects an individual goes far beyond the physical. It is not just a matter of weakness or knots in the stomach, but about devilish transformations in the psyche.

When things go well, wealth and accompanying privilege can cushion all of life’s woes. But, when hunger strikes, the cushion is ripped apart and nothing protects you anymore. The richest man in the village becomes a hapless target of people’s ire as they start suspecting him of hoarding grains. Suspicion grows virulently in such conditions, turning into rage. Suddenly the rich man becomes the hunted man. His hangers-on become his attackers. Looking well-fed and rosy cheeks are a liability, no longer something to be proud of.

And how do you hide your food when the appearance of your health gives you away? One cannot eat and also lose weight. One cannot sneak in a few morsels at meal times and also show people you are wasting away like them. Weakness from hunger can steal away your life, but not looking weak from hunger can have your life stolen from you.

Even a chaste woman can cross the previously unthinkable line between staying with her husband and leaving him for another man. When Chutki finds her stalker has ready access to food, she initiates an affair with him in return for handfuls of rice. This woman is capable of fighting off any attacker except hunger. She killed someone who attacked Ananga, but now she cannot fight for her own dignity. After all, it may be pointless to defend a body that may any day be separated from you.

Those who aren’t outright killed by hunger are permanently changed by it. It is a fact that in such extreme situations, people have been known to resort to eating garbage, licking used vessels, hunting rats, and even turning to cannibalism. Such ugliness is unleashed by hunger as can hardly be imagined. Yet this happens. And it happens even to those used to high standards of life.

One is used to hearing stories of people stranded on icy mountains, after a plane crash or an avalanche, resorting to such acts. It feels like such distant occurrences, as can never be part of our unadventurous reality. But over three million were affected by this famine alone. With such numbers it’s hard to be confident that, had we been around, we would have been spared.

Fighting An Unseen Enemy

Despite such horrific images what is actually unbelievable is that so many people didn’t descend into chaos and utter degradation. Like the untouchable woman who dies because she is unable to feed herself, many people accept their fate without resistance.

How is it that they didn’t break into anyone’s home and steal what little he had?

Why didn’t the downtrodden rise up in violent rebellion to bleed the rich hoarders of their grains?

How could groups of people just silently wait for someone to take pity on them?

The fact is that too many members of human society have been made to accept this as their destiny. The operative word is ‘made’. Their social and political leaders, their teachers, their religious texts, and even their law-makers, have ingrained servility in them over centuries. They are like chickens in coops. Never fighting, never fleeing, just a few squawks before death.

The unseen enemy that is hunger, also has unseen allies. The great war was something most Indians never even heard of, and the British authorities who engineered this famine for their interests were operating from far distant shores. Scarcity itself crept up unseen, as this wasn’t a natural famine.

When all causes are invisible and only the effects are visible, then what agency can these poorest of folk grab for themselves? Rise up against injustice, they can. Rise up against politicians, they can. Rise up against criminals, they can. But how do they rise up against hunger?

Then all they can do is appeal to invisible forces of divinity, generosity, luck. But, unlike the unseen enemies, none of these actually exist. These will not come to their aid. And they may lie waiting for help, it won’t come, and they will slowly cease to exist.

Human degradation, when it has been instilled into you for centuries, can make even victimisation appear justified to the victims. Of course, no small part is played by the fact that the most vulnerable people are also the ones who are immediately disarmed. They cannot fight even if one of them tries.

If they raise a hand it will be chopped off, so they just cup their hands to receive alms.

Even though hunger spares no one, some people are still a little more fire-resistant than others. The bonier, malnourished bodies burn like dry tinder. The fact remains that Gangacharan and Ananga can look forward to having a child even under such dire conditions, while others may have to bury theirs.

The fact also remains that even when experiencing every bit of the horror of the famine, Ananga is still unable to actually feed a dying untouchable, leaving her to her fate in the fields. The privileged will not experience this degradation. They will watch it. And they will believe their destiny is to survive, while the lowest strata will believe their destiny is to die.