THE IDLE-ISED WOMAN

The original title under which Rabindranath Tagore published this story was Nashtanirh, or the Destroyed Nest. Many consider the story autobiographical of his own relationship with his sister-in-law and how it was a source of, both, joy and desolation in his life.

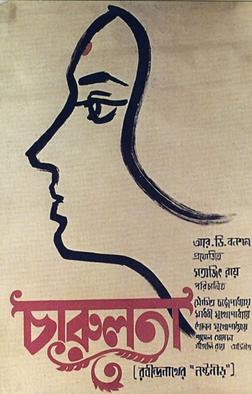

We don’t need to know if any of this story, filmed under the title Charulata by Satyajit Ray, is true to factual events. What does matter is that even today, watching a character like Charulata (a once-in-a-lifetime performance by Madhabi Mukherjee) can evoke in us feelings of injustice about how some brilliant minds have been overshadowed by their social roles. Charulata represents all women who had so much talent to offer the world, but were either hidden away or chose to hide away.

One of the best period films of India, Charulata opts out of any grand historical narrative of its time (unlike Shatranj Ke Khiladi) and pulls its focus so close as to get right into the psyche of this timeless woman. So many Charulatas have existed over time, and continue to exist, that any viewer should be able to turn their mind’s camera to the narratives of women in their lives with equal aplomb and sensitivity.

Constricted And Constructed

Towards the start of the film Charulata is the iconic bored housewife, firmly cushioned amongst the upper crust. She is a member of the aristocracy with dozens of staff to do her every bidding. She has no work, at home or outside, and consequently is shown wandering around, reading, or looking out the windows with her ornate binoculars. She goes window-to-window watching a rotund man passing her house as if she is turning pages in a book. The windows are both a way to look out at the world and a limiting viewpoint.

Even though each one of us may envy her lifestyle, it is quite clear what kind of constricted life she leads. The movie situates itself at the start of the twentieth century (the book was even earlier) and by that period setting we already know a lot about the restraints on Charulata. She would be living in purdah, prohibited from meeting men outside the family. Going out alone would be too outrageous to even imagine, and even going out with chaperones was not likely unless it was for important functions or places of worship. In fact, being literate and reading novels was a fairly new allowance for women at this time, and it is only her advanced social status that gains her this privilege.

Literature and the other arts are dangerous things, aren’t they? They open minds that have been forced tightly shut for so long. They instigate sinister thoughts of liberty, humanity, and individuality. So if we are surprised by Charulata’s restlessness, we can immediate ascertain the cause of it when we first see her with a book. Even when she embroiders, one of her fond hobbies, she chooses to include lettering in her patterns as if it is another chance to engage with the written word.

This is a woman who has read and felt things in her mind that no one else may know. Like any book-lover she would have gotten lost in thought between lines, her mind going from where to God-knows-where. She would have travelled, interacted, even been seduced in her thoughts in ways no observer could know. Charulata, the well-read woman, has tasted the forbidden fruit and wants more.

Of course, her privilege is not everyone’s. As mentioned, her social class gives her access to education and to her husband’s personal library. In fact, Bhupati is a progressive man who believes in the power of literacy and encourages his wife to read, and later to even write. He is wealthy, but not idle, choosing to use his means to run a progressive newspaper for the betterment of his people. Bhupati, like Nikhilesh in Ghare-Baire, and like Tagore himself (creator of both these characters), is a conscientious aristocrat, ergo one who uses his wealth and privilege for social upliftment. (Whether such a person can actually exist is a matter for another essay.) He enforces no restrictions on her directly, though indirectly there would be more than meets the eye.

A lot of time is spent in the film showing us things through Charulata’s viewpoint, rising to its greatest height when the camera is right on a swing with her and rises and falls to show us the world through her eyes. As a result, the film never lets us leave the estate, only farthest venturing out to the gardens.

Can a woman like her ever be satisfied by just this? Can any woman? Even without knowing the rest of the story Ray has gotten us to identify with her, almost tangibly, and experience some of the suffocation of what it must be like to live in a gilded cage.

And it is exactly this gilded cage that gets disturbed by a sudden storm.

The Brain Wants What It Wants

Amal, her husband’s cousin brother, arrives as a whirlwind of creative energy and youthfulness in their lives. Many have identified the storm as representative of the wild energy of Amar’s character, but it is not. It is the destruction that follows him. He is not guilty of it, but it comes with him nevertheless – the storm that will destroy this nest.

Symbolically, Charulata is holding a pair of caged birds and about to take them to the safety of her room when she sees the exuberant Amal has arrived. Even though she has been trying to stop the outside world from invading her home through the windows, he is a force of nature that cannot be stopped.

Soon enough, we see some form of attraction in Charulata’s eyes for Amal. For a while we may wonder whether it is of a physical nature, but soon enough we reject that notion. There are times when the two of them are alone together but the interactions don’t have the edginess of any sexual tension. Rather, what we witness is much more maternal on her part, seeking to pamper this young brother-in-law and not seduce him. She wants him all to herself, not as a lover, but as a conversationist. On his part, Amal is the kind of man who isn’t used to taking care of himself and welcomes the watchful eye of his sister-in-law.

She buys him gifts, repairs his clothes, fawns over his talents as a writer, and longingly gazes at him. Despite all of this, the viewer is left uncomfortable, because one cannot help but notice the desire in her eyes. There is hunger in her, of a kind that doesn’t make itself known explicitly. It comes out when they share light-hearted conversation, or get excited over readings of poetry. It belies how famished she is for two things in her life, two needs that a man other than her husband is fulfilling – attention and intellectual stimulation.

This is not a person who seeks carnal knowledge but intellectual knowledge. Her unmet needs are not like those of others. When she ogles Amal through her binoculars it is when he is immersed in the creative act of writing (tellingly, it is the brainy part of his head that occupies the greater part of the screen, not the face). She has a powerful mind, a strong spirit, she is not content staying indoors all her life. And what’s wrong with that? The world is an enormous place, and like birds, our bodies and souls want to traverse greats lengths of it.

Since Amal is on holiday, between college and finding a job, he has a lot of time to give her. In fact, it is Bhupati’s request to his cousin to spend time with Charulata and give her some companionship that she lacks. Though his office is in the same house, husband and wife’s paths don’t cross for many hours of the day. And he is a man consumed by his work, stimulated by it like Charulata wants to be stimulated by learning. His newspaper is a competitor for his attention and usually gets more of it than his wife. In an act of short-sightedness he turns his wife’s needs over to someone else, and none of the three are prepared for the fall-out of that.

In contemporary times, the word sapiosexual desire has gained popularity. It refers to an attraction that is based in the brain, instead of in the heart or body. In other words, one is aroused by somebody else’s intelligence and not their appearance or shared experience. Long before this came into vogue, we had Charulata, and even longer before that we have always had women and men pining for the fulfilment of their intellectual needs.

Even the fights that Charulata and Amal have are over something like whether or not to publish poems. She has obvious talent that is at par with any of the published writers they read, but just getting praise from Amal is good enough for her. She doesn’t desire any public recognition or reward. In fact, she is more concerned with making a beautiful notebook for him to write in, as if to say she prefers being the receiver, not the writer.

This is probably because her sights are on much humbler prizes at first. And only after some initial satisfaction can anyone in her position think bigger. Amal, on his part, is a little threatened by her talent. As an aspiring writer, he has the same insecurities that any of us have, that she will outshine him and take away what he views as his right.

When she and Amal fight, she strikes a blow in the form of publishing her poetry against his wishes. She does this intentionally to injure him for withholding his attention from her. This makes him uncomfortable and he takes it as a kind of betrayal. Further, she aggressively celebrates her victory for forcing one of her hand-made paans into his mouth. We can see Amal thinks a line has been crossed, while Charulata never realised one was ever there. Even her intellect is chastised for trying to leave its cage. Ironically, when Bhupati finds out from his friends that his wife’s brilliant poem has been published, he is actually delighted. At the same time, he is surprised she didn’t tell him this herself. He realises, a little too late, that his wife conceals an immense part of herself from him.

Freeze Frame

Amal’s sudden departure leaves her even more desolate than before. Her mind has experienced joys in these few days that she will never again have. She sees he has left behind one of her gifts to him, a clear rejection of her feelings, and she mourns her loss with bitter tears. Her husband finally realises that he has allowed too great a distance to build between him and his wife. He sees his wife pining for another man and is thunderstruck.

His beloved newspaper receives a fatal blow when his business partner embezzles funds from it and escapes. It feels like the death of the paper is the impetus that he needed to return to his wife. They are both people who have been betrayed by the little worlds they tried to create out of nothing but good intentions.

Even at this lowest point it is she who offers him hope in the form of her suggestion to revive newspaper with her as his editorial partner Alas, if Bhupati had only realised a little sooner that he needed to make sure his strongest partnership was well-nurtured on steady attention and not just intention, he would have a source of strength to fall back on. As things stand, who knows if they can put the past behind them.

The film ends on a freeze frame, with wife and husband stuck for eternity in a space between reconciliation and suspicion. The picture is revealed in details and then in its entirety as the viewer is suddenly pushed back from their former intimate closeness. After such a long journey sitting so close by Charulata suddenly we are flung out of her life, never to know what happens.

The unfortunate woman, on whom this story may be based, took her own life. There is no reason to believe there is any similarity between this story and hers, but it indicates the darkest ending that could be given to this story.

But, Ray is a sensitive enough filmmaker, a genius really, that he realises this is not a story that can be given any ending by him. Charulata is not merely a fictional creation, she is one of his most fleshed out players. Many consider her the best character out of all his films, and it’s hard to disagree. And no amount of credit can be enough for Mukherjee for her portrayal. One almost imagines that we have been watching a documentary, or a reality show, and this is the point that the cameras have been turned away by Charulata, the point beyond which Ray cannot transgress.

In another way, Ray is asking us to imagine our own ending for her. He cannot complete her story, it feels wrong. Given the chance, can we? Can we imagine her and Bhupati reconciling? Do we wish for Amal to return? Will she write again? Will wife-husband go into business together? Like many couples will they reunite through a child?

The possibilities are endless, and yet time has frozen on Charulata’s story leaving her in eternal limbo.