BENGALI ZOETROPE

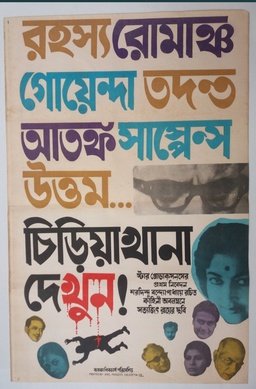

A boarding house of destitute and desperate people, each housed in their own enclosure, identified by their specific habits and histories – welcome to the Chiriakhana. Satyajit Ray’s first foray into detective films (to be followed later by his two Feluda films, based on stories he wrote himself) was a rather uncharacteristic film.

Known as a maker of ‘serious’ art-house cinema, this was a heavily mainstream film, featuring none of the identifiable features of the rest of his oeuvre (as can also be said of the film Abhijaan). Or so it may seem at first glance. Even though it isn’t one of his best works, it is still a film that manages to offer something fresh in the heavily-populated genre of detective cinema.

The Detective As Zoologist

The film is an adaptation of a story by Saradindu Bandhyopadhyay and features the famous Bengali detective Byomkesh Bakshi (who would be replaced from his throne by Ray’s own Feluda later). In the film Bakshi is played by Uttam Kumar, who had appeared in another Ray film, Nayak, just one year prior.

From the very start of the film, Bakshi is shown as a man with a zoological approach to mystery-solving. He is shown handling a snake he keeps at home, enamoured by the slithering sensuality of the creature. Clearly he is not afraid to get into striking distance of danger because he knows just how to thrust and parry. By being observant, the detective’s greatest asset, Bakshi can catch a killer and sidestep any traps even while escaping observation himself.

The story makes the connection between the detective and a zoologist explicit by situating the mystery largely in the environs of a horticultural-nursery-cum-boarding-house (flora and fauna) run by the murder victim. The victim had a long career as a judge, and spent his retirement years trying to rehabilitate those in need of help as a way to compensate for the many harsh sentences he passed during his days at court. When he is murdered, presumably by someone whose life he had impacted by his decisions, it seems as if the hunter has become the hunted.

Playing out the rogue’s gallery trope of the detective genre, Bakshi goes hut-to-hut on the estate to interview each of the inmates. Each for their reason is trapped here, not by the judge but by their own past traumas. Somebody is a reformed thief trying to make good on his promise to society, somebody is a disgraced doctor, somebody lost all their money and has nowhere to go, somebody is a widow with no source of support, and so on. Each person is given a set of defining characteristics, and we as the audience hold on to these as probable identifiers of the killer. Like bird-watchers or big cat trackers, we hope to be able to catch the killer just by sound or pug-marks.

Interestingly, the keen viewer is invited to move beyond just listening to Bakshi and to start studying Bakshi himself. Bakshi’s residence is constructed with much care and seems to be a representation of the man’s past record as a mystery-solver and also reveals his personality. Apart from the obvious presence of poisonous animals, there is a replica human skeleton, a collection of shop-window notices, a city map. He too is a creature in his natural habitat and we are invited to look for the signs in him and around him. Watching him interact with his companion, with the caretaker, with the client, we start to prepare our own file on him. [Applying this approach is actually very rewarding on all of Ray’s films.]

Of course, Bakshi is not the only renowned fictional detective who deploys this zoological approach. Even in the real world, Police investigate crimes based on stitching together a wide range of evidence to make an air-tight case. This has to further be presented and defended in a court of law and withstand scrutiny. Character assessments and circumstantial evidence is quickly dispensed with as they don’t prove anything beyond a doubt. What this film achieves is to present this particular aspect of detective work exceedingly well.

In a lot of detective fiction, however, the detective’s approach is to put suspects under a lab light to see if they accidentally implicate themselves. Much of this hinges on ascertaining criminal intent. How much of this would pass muster in an actual court of law is not something I am qualified to state, but suffice it to say that this guilty-until-proven-innocent approach can be very unstable.

But, detective fiction is not all about procedure but also about suspense and dread. And that’s why the zoological approach works so well. By creating a menagerie of potentially deadly animals and dropping the detective in there armed with a whip and his steely stare raises the stakes manifold. The fact that being a private investigator offers him none of the protection that a Police uniform would offer means he is perpetually in mortal danger.

Eventually, it is that inmate who routinely leaves the zoo who is revealed to be the killer. He is the only one who is still running wild, not fully caught and caged by society or the judicial system. He is the one the zoologist is after – the wild beast who leaves the sanctuary and becomes a threat to the men and women outside. The detective is the licensed hunter, after all, and he wants to ensure the dangerous subjects are placed in an even tighter zoo cell.

Concealing And Revealing

It is hard to see Uttam Kumar as Byomkesh Bakshi go undercover as a Japanese horticulturalist and not be recognised. It is even harder to see the inmate who was once an actress, and not immediately recognise her just because she wears a fake nose.

Detective fiction, whether on film or in books, entirely stands on the creator’s skill for concealing and revealing information to the reader in bits. After all, too much information can make the film boring because people will guess the ending beforehand. Too little will also be boring because the audience feels excluded and unwanted on the mental expedition.

There are major differences in how this can be achieved through the disparate mediums of film and literature, and how the gap between them needs to be bridged by a good adaptation.

For instance, whereas written descriptions of people’s faces can be limited to only a few features, on film one is forced to reveal the entire person, and hence more than what may be needed. A writer can describe just a nose, but the film cannot show just the nose except in very absurd ways. Similarly, in a book we can go along with the assumption that a detective may easily blend into a crowd and not be recognised. But in a film, every pair of eyes in the auditorium instantly zooms in on the magnetic face of Kumar, making it impossible for him to stay out of sight.

To solve a mystery dramatically there has to be a mix of sharp reasoning, sudden coincidences, unlucky slips, and finally a confession. All of these play out very differently in different media and that’s what makes the art of adaptation unusually difficult for this genre. There are many examples across the world of this.

This game of conceal-and-reveal plays out much more through the technical aspects of cinema than, say, the poetic. Carefully crafted art design and cinematography becomes the best way to achieve this. Shadows falling on a person may no longer be just about mood, but can cleverly conceal the killer’s face. Music in the background is not just soundtrack, but can affix the presence of a person at a specific place and time. Everything that is usually mood-enhancing in any other film, becomes mystery-enhancing in this film.

And that would be why many people find this film to be not up to the high standards of Ray. The criticism that comes its way is because it falters in adapting from one medium to another. It is somewhat perplexing that someone as particular and having an eye-for-detail could not foresee and avoid these errors. How or why that happened is not in my capacity to say.

But, the rest of the film is a very carefully constructed work and Ray shows his excellence in casting choices, the presentation of his characters, the strong presentation of film noir elements to create mood, and above all his enduring love for the mystery genre.

Even though his Feluda films are remembered more fondly (this could be because they are a part of many viewers’ childhood days while this film is for older viewers), Chiriakhana is Ray’s most painstaking jab at creating a great detective feature film. And but for a few missteps, it could have been his greatest.