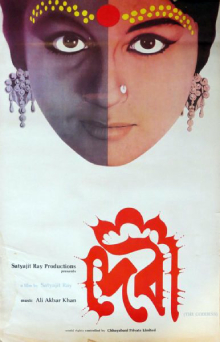

THE GOD-MOTHER

Among Bengalis there is a peculiar tendency to use the word Ma, meaning mother, to address not just our birth mothers, but also goddesses, daughters, sons, daughters-in-law, and generally as a term of affection that borders on devotion. It is likely to sound strange to non-Bengalis, and yet it is the most natural and comfortable form of address among close relations.

The audience cannot be blamed for getting lost in symbols and semantics when one character in Satyajit Ray’s Devi praises his daughter-in-law by saying, “When I utter ‘Mother’, Mother herself appears before me – how many are so blessed to have such a Mother, tell me Mother?”

And yet this film also makes clear that different kinds of Mother are not treated the same when it seems that they may overlap more than just in our affections. From this idea the writer, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyay, weaves a masterful story of present-day divinity which Ray turns into one of his most compelling cinematic masterpieces.

Keeping The Faith

Faith and religion are often used interchangeably, but they don’t seem to be the same. Religion is a much more outwardly form of observance, external to our being, while faith is internal. Religion only pertains to matters of worship and prescribed rituals, whereas faith is the response of one’s spirit to one’s experience. Religion needs faith, but not vice-versa. Religion is easy to decry when it begins to show imbalances, but when faith starts to show cause for interrogation it actually grows even stronger.

When young Daya is declared as an incarnation of the goddess Kali she is caught between her faith and that of her father-in-law. But while her father-in-law, Kalikinkar’s, faith comes from the dream he had, hers comes from her upbringing, her respect for him, and to not offend his position as patriarch. She cannot reject his belief even if that starts her on a path to mental anguish. That’s her faith in the unimpeachable wisdom of her elders. Kalikinkar himself is so beholden to the benign presence of women in his life, first his wife and then his daughter-in-law, that he cannot dismiss his own dream as just a dream. His true affection becomes mixed with his faith and can no longer be shaken.

There is an elder daughter-in-law in the household too, but since she didn’t appear in a dream her divinity is never considered. In fact, there is a character in the film who is disinherited entirely by his father just because he has intentions to marry a widow. That shows us how there are many ways that women can fall in such a society, and hardly any in which they can rise.

Daya is lucky because her innate nature is such that it meets all the requirements of a good, homely wife. Is her appearing in the dream just chance, or is it because she is more deferential and hence easier to mould into a goddess?

After she silently accepts the faith directed towards her, Daya becomes like an actual stone idol, sitting motionless on a pedestal while worship is directed at her. Where one places an idol to stand in for the goddess, here we seem to have put a woman in place of an idol.

The die is cast once and for all when a terminally ill child appears to recover, miraculously, when given some spoons of holy liquid in the presence of Daya. This is evidence and everyone has witnessed it. The person most perplexed by what transpires is the goddess herself, Daya. This is the moment when she starts to have doubts about her own humanness.

And I use the word ‘doubt’, purposefully. Till this point Daya is just going along with the show like a terrified child thrust on stage, but when this miracle occurs the words of the others start to gain credibility. This portends to become unbearable because she is not the kind of human being who can function with that kind of self-knowledge – that she may have the power, and responsibility, to give life to dying people.

While there are religious paraphernalia surrounding her, what makes the faith in incarnation irresistible is the impact on actual human lives. Even the most agnostic or atheist among us, and that includes me, will find it hard to reject someone who has placed their entire faith in our ability to help them out of dire circumstances (none of the people, including her father-in-law, who have elevated this young woman to this untenable position are ruthless exploiters, like Birinchi Baba, out to make a quick buck at the expense of the believers). This is especially so if we have no practical solution to offer, only the reciprocation of that faith. It is out of kindness we may do that. But young Daya is unable to balance what she sees with what she believes with what she wants to believe. And the one person in the household with whom she can speak her mind, her husband Uma, is away finishing his studies during this time.

Later when Uma comes to know of what has transpired, he returns and persuades her to run away with him and escape those whose faith have imprisoned her and cut her off from her normal, natural life. She agrees at first but then changes her mind. She is afraid that in case she really is a goddess, her husband’s transgression in stealing her away from her devotees will damn him. She is afraid that if she really is a goddess, the goddess will curse him. Her psyche has fractured so definitively that she is performing two or more roles of Mother at the same time. She is torn between her faith in her husband and in divine retribution. She is afraid of her own power.

We all have faith in many things – faith that hard work is rewarded, that we can overcome all odds, that there is true love out there for us all, that we will have long lives and peaceful deaths, that our civilization will not collapse, that our home is our safe space, and much more. But at least some of these will be shaken or even overturned during the course of our lives. How then is one supposed to respond to what remains? How do we know which channels of faith to discard and which to retain? Or does it have to be all or nothing?

Negotiating with our faith is one of the toughest things we have to do as mature human beings. It is the reason that facing death at close quarters is something we can never get used to even though it has been a fact of life since life itself. That is why when faced with the cruel mortality that haunts our every step even non-believers find themselves calling out to the power of faith.

Worship Is Work

Faith is integral to our lives, faith is empowering, faith gives us lifelong succour and support. Why then can it also destroy us like it destroys Daya and her family?

When the film begins we see that there is something special about Daya even before Kalikinkar’s dream starts the avalanche. She is beloved of children and animals – her nephew seems to love her more than even his own mother and their pet parrot waits for her loving caress. Her husband is enamoured of her. In short, everybody finds her presence to be illuminating and joyful. Isn’t this divine enough?

Her relationship with Uma has the bounce of youthful love. They are intimate with each other only as soulmates can be, and yearn for each other when separated. All indications are that they will have a beautiful life together where every day will bring tender affection and new adventures. Isn’t this divine enough?

Her loving nature towards everyone, including her aged father-in-law, provides emotional and spiritual healing. While she is still young her effect on others is motherly and nurturing in these ways, which is why she is called Mother. People like her bring colour to the world and also coolness against harsh realities. Isn’t this divine enough?

The thing about faith is that it can simultaneously be universal and also inadequate for humans. Just seeing nature, happiness, love, and thoughtfulness seems to be insufficient evidence that we are all enjoying divine beauty. The sun and the sky, the deer and the tiger, the arts and the sciences, all seem to be insufficient proof of grandeur, and what we really want is a miracle. And we want it on command.

When you take a delicate and good-natured woman from her free surroundings and then place her on a pedestal from where she cannot move, what divinity is that? To heap heavy garlands on her, to subject her to the wails of children over whose health she has no power, to expect her to perform miracles, what devotion is that? When she is separated from her husband, unable to know the love of a touch or a kiss, and then also separated from her loving nephew who is now too scared to enter her godly room, what life is that?

When the inner experience of faith becomes nailed to the boards of ritual then how can it show itself? Daya was no less of a miracle before Kalikinkar’s vision, as he himself stated in effusive praise. An animal in the wild is as much a miracle as a performing animal in the circus. Just because it doesn’t parade under our constant gaze doesn’t mean its existence isn’t precious.

Unfortunately we see the tangible world and the divine world as two distinct things and that we must demote one to promote the other. While monks may find this necessary for their extreme spiritual practice, it should not be a need felt in the lives of common folk. Promoting goodness in the world is a greater spiritual service than only chanting prayers.

One is certain that if woebegone parents had brought their paralysed child to Daya for help she wouldn’t have turned them away, even if she wasn’t enthroned. She may, if she was inclined, have chosen a life of social service, encouraged and aided by her husband, where she could have gone to the people to help them instead of them lining up to catch a glimpse of her on her perch (like her chained parrot).

Good work, goddesses’ work, can be done by human beings. We can recognise divinity all around us, even witness miracles, but why must we capture it in a bottle? A belief in a higher power doesn’t mean we deny the life we have been granted by it. To live a good life, too, is divine.

When Daya is unable to save her own nephew from death, suddenly she becomes the cause of his death – since she had the power to save him, then she must not have wanted him to survive. It is not her fault that others entrusted him to her care and she too came to believe in miracles. When the doctor summoned by the mother of the ailing child refers his case to Daya, all is lost. Everybody must share the same act of faith else it withers. Faith takes the form of conformity.

When he dies due to lack of timely medical care, it is their collective faith psychosis that has struck the fatal blow.

Daya, unable to cope with the death of the child, descends into madness. The loop is closed. After the conclusion of goddess and god worship festivals, it is customary to immerse the clay idol in water, where it dissolves. That which took form and stayed with us for a few glorious days, again becomes formless and goes back to the elements. Daya, too, feels it is time for her to leave. But in her case it is because she is suddenly more demoness than goddess, bringer of death than life, neither of which was or will ever be true. She races away from her husband and the entire household and leaps into the water. She wants to become formless, lifeless.

It’s a strange thing about faith that when it is at its weakest, we become ever more determined to stand by it. We close our eyes. Our faith become blind. We must feed it with our belief because it is all we have left. And perhaps that’s when even our faith feels too overwhelmed by our plaintive desperation and decides to abandon us.