TYRANNY OF THE MAJORITY

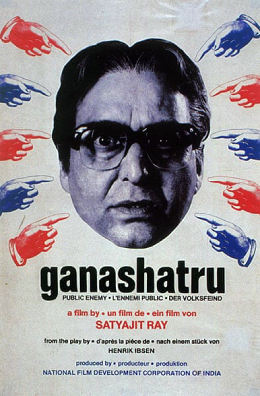

It is the sign of the highest levels of humanism in a writer when they tell a story that can be situated in any part of the world and still hold true. Such is the case with the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen whose 1882 play En Folkefiendecould be so fluently translated into Satyajit Ray’s 1990 film Ganashatru. In fact, I would argue even a film like Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is an (unconscious) retelling of the same story. What a work of genius that can be moved from icy Scandinavia, to coastal America, and sweltering India, and lose nothing in human experience!

Married To The Mob

While we are all familiar with the concept of democracy, I recently learned the termed ochlocracy. This is a system of governance which is led by a mob, or more simply put – mob rule. What this means is a system where decisions are made by the brute power of a mob (not an individual).

Of course, this is not a practised form of governance, but rather a perversion of the ideals of democracy. The evil twin. And since no member of a mob realises that’s what they are, the quandary is to know when society has decisively moved from democracy to ochlocracy. Unlike individual lifetimes, there are no defining moments in the lifetime of a society. There are no collective epiphanies or eureka moments. The biggest changes can be imperceptible.

The more pessimistic among us may feel that from the moment of its inception a democracy is susceptible to this perversion. After all, rule of the people (democracy) and rule of the majority (ochlocracy) sound almost the same, behave almost the same, and have the same validity in matters of state. Since there is probably no topic on which there exists one hundred percent agreement across individuals, majority rule is the practical form of democracy.

But, human nature seems to abhor ideals of collective wellness, and settles for personal gain more often. One is loath to sacrifice for greater good, especially in esoteric and long-term situations. It is very nice to imagine a person planting a sapling to grow into a tree that will benefit others, in whose shade they will never get to sit. But how many of us are actually likely or capable of thinking like that? Isn’t it more likely that we will cut down a tree that blocks the sunlight to our living-rooms and then block someone else’s sunlight with our illegal extensions? And even if we aren’t evil by nature, the growing tussle for space in human settlements means that it’s not even possible to take a step in any direction without blocking someone else’s path.

When the doctor Ashoke finds many of his patients are suffering from jaundice, he narrows the cause down to infected holy water distributed at a local temple. Alarmed by the looming danger of a massive outbreak among the temple-going population, he immediately alerts the authorities to shut the temple down till the water supply can be made safe again.

This is an undertaking that could take weeks, and also bring the interference of science into the domain of faith. Can holy water be infectious? After all, it has been blessed by the gods and is an elixir that is consumed to protect your health and not harm it. Also, it’s in the nature of sceptics to try and dilute the power of faith, is it not?

This is the dilemma faced by Ashoke, a man who wants to discharge his responsibility of keeping the public healthy, while that very public is goaded by vested interests to distrust him. Suddenly a very straightforward matter of water-borne infection spirals into a science versus religion debate, and that’s when the ‘rule by the people’ morphs into a ‘rule by the people, against the people’.

Ashoke tries to appeal to the administration to shut down the temple, and fails. Then he tries to use the press to make the public aware of the risks, and fails. Finally, he goes directly to the people and organises a public forum to speak his mind directly, and even after that he fails. It seems the people are just not willing to take him at his word. They are convinced there is no risk from holy water, the same that they have consumed all their lives and so have their forebears. They cannot fathom that modern techniques make it possible to see the evidence which wasn’t visible earlier. They believe in unanalysed experience and not expert knowledge.

This was the warning that philosophers as far back as Socrates, and even further, sounded about democracy. Rule by the people has been compared to letting passengers, and not skilled pilots, fly aeroplanes. In other words, rule of majority, usually when the majority are not sufficiently informed on important subjects, or sufficiently able to see beyond their own needs and towards collective good, cannot take correct decisions. People of faith should not have a bigger say in public health matters than a medical expert (who may or may not be a person of faith themselves).

But the vehement opposition to Ashoke, fanned by the mischievous manipulation of politicians, can turn a people against their own self-interest, pushing them further down the road of anti-rationalism and sectarianism. Important decisions become framed in an ‘Us versus Them’ false dichotomy, instead of ‘Us and Us’ wisdom.

In this way, Ganashatru forms an interesting opposite to Ray’s other film, Hirak Rajar Deshe. In both cases, an informed and unbiased benefactor of society, (both times played by Soumitra Chatterjee), tries to lead his fellow citizens away from destruction and towards freedom. But, in one of them the people accept his leadership in the matter and follow him, in the other they reject him and unwittingly gamble against their self-interest. And, mind you, this is not a subjective self-interest where what’s good for one may be bad for another. This is purely scientific: bacteria and disease are bad for all.

What can one do, then, for a society committed to bringing harm upon themselves? Is this rule by the people the best system of governance we can hope for? It is certainly better than any kind of authoritarianism or fascism, and yet it is so poor at protecting basic human rights.

It was Plato who proposed the rule of Philosopher-Kings, meaning people who rule unilaterally as kings, but who are endowed with wisdom and far-reaching vision, who can assemble the best of all minds and skills to tackle any given situation. In the case of Ganashatru, Ashoke would be the ideal candidate for the job.

Yet, it is also an impracticable solution, one that relies on some way to evaluate the myriad aspects of wisdom and also confirm the absence of authoritarianism and tyranny. Moreover, it is my belief that the ideal candidate would necessarily also be someone who doesn’t want to rule over others and will not sacrifice their chosen paths in favour of politics. Ashoke as ruler, though ideal, is also improbable.

Moreover, just like it is the victors who write history, it will be the king who defines philosophy. The rule of a Philosopher-King is at once the best, and most impossible, of governments.

At the end, Ashoke does what he must. He takes the browbeating because he cannot shirk his duty. But, finally, he cannot compel people with brute power to agree with what he is saying. People are free to live or die as per their choice.

The Health Of The Economy

Ibsen’s story also points out the very lopsided architecture of human society – the economy must be protected even at the cost of society. Whether it is the tourist season in Jaws, the revenue from the spa in En Folkefiende, or the revenue from the temple tourists in Ganashatru, the obstacle in the way of public welfare is always one simple thing – money.

And this is not just a matter of fiction, because we have seen many examples around the world that support this reading, from the aftermath of the stock market crash in 2008, to the fallout of the Covid pandemic in 2020, and many more. Every time there is some kind of disaster, it pits human lives against the nation’s wealth, and we process grim calculations to see how many deaths are acceptable in order to preserve what quantity of wealth. Daily wage earners have to weigh the chances of dying from a disease against the chances of dying from hunger or ending up homeless.

Ashoke’s own brother, Nishith, does all he can to prevent the doctor from achieving his objective, even if this means instigating the crowds against him. Matters go so far as to threaten Ashoke and his family’s safety when mobs start stoning his home. Through deft manoeuvring of the narrative, even a mediocre politician can run circles around the most qualified professional, especially a guileless one.

Strangely, despite the common people being religious they can easily be swayed by evil leaders to turn against the one who is most faithfully doing good. And this is because people don’t so much think about right or wrong when it comes to practicing religion, just ‘Us versus Them’, and this is what Nishith can take advantage of.

And the most frustrating thing of all is that the good doctor has no intention of permanently shutting down the temple, or preventing the worshippers from returning to their practice. He simply wants prohibition until the problem is resolved. That this much cannot be done in the interest of the people shows whose interests are actually at stake.

Nishith’s own purpose is the continued earning of revenue through temple donations (a holy cash cow, as it were). If the medical evidence linking the disease to the Holy Water can be covered up, or even debunked, then it boils down to winning an argument with showmanship and nothing is better for the politician.

There is a sliver of hope for Ashoke though, when he gets a show of support, among the many rocks and bricks, from the few who still believe in public health and medical science. He is invigorated by the prospect that even with a few supporters he can save the town. Alas, while one desperately wants this to be true for the good doctor, it is still far from over. When one side is lobbing grenades, the other side is relying on words. This is a hard battle to win.

What then can be said of the wisdom of the people and the tyranny of the masses? Is democracy doomed to fail at protecting itself? The answer can be found in Hirak Rajar Deshe – education.

Democracy relies on its people being fully informed, not just in facts but also consequences. Rulers who wish to grab power always try to keep their subjects in the dark, either denying them information or giving them what is rotten and untrue. The kings rewrite history and philosophy to favour themselves, setting themselves up as descendants of gods and arbiters of our destiny. To be able to live as true democratic subjects it is necessary to rise above sectarian issues, adopt modern thinking, and envision a future that is balanced and nurturing. People need to realise they are part of a very wide network of nature, and to be torn apart by fighting over holy water can be the most unnatural state of all.

Only by listening to the true friends of the people can the enemy be defeated. Otherwise the people themselves will end up becoming the enemy.