ANGELS RUSH IN WHERE FOOLS FEAR TO TREAD

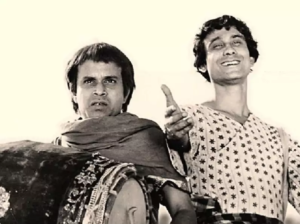

The maker of the Apu Trilogy is also the man behind a 7-minute long comic operatic sequence involving ghosts playing out the history of British colonialism in Bengal for the entertainment of children. Such are the stuff of dreams and one of Satyajit Ray’s most beloved films. Many of Ray’s fans outside Bengal may not be aware of his enormous contributions to the corpus of children’s cinema, nevertheless Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne is still a favourite with young Bengali audiences and a heavy nostalgia trip for their elders. It is a tradition during school holidays to watch this film on television, along with its sequel Hirak Rajar Deshe.

The original characters, on whom the film is based, were conceived by Ray’s own grandfather Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury back in 1915. Though surprising at first, it is plain to see how coming from a family of children’s story writers would have inspired Ray. In fact, it is not the children’s movies that should be considered the anomaly in his oeuvre, but those he made for adults.

And Justice For All

Just because the film creates a world of absolute play one should not hold the mistaken notion that the story cannot contain kernels of very profound truth. Children’s stories are, after all, products of mature human minds and therefore modelled on human concerns.

When Goopy and Bagha set out to prevent a war between two kingdoms they also lead the viewers into ideas of justice and diplomacy. That two simpletons like them can play any role in preventing armed conflict is a noble thought to begin with. It shows the capacity each of us has to create a lasting influence on the world around us just by being good human beings. Of course, it cannot be forgotten that they have special powers that place them beyond normal human capacities, but the film also makes it clear that they are given these powers on the basis of their moral fibre and nothing else. To have such awesome magic and to use it for good is the combination that works, and only for them.

The duo aren’t selfish about what they have and don’t hesitate to help others. They know that a war can be won through food, without shedding blood, because they can see how hungry and emaciated the soldiers are. Alas, all too often we can lose sight of the individuals who are being thrown into mortal danger on behalf of others. To see the humans in the conflict is probably Goopy-Bagha’s most special power.

While it is wondrous for young audiences to see the world of kings and princes, spirits and sorcery, the film doesn’t lose sight of those unfortunate people who inhabit the same world but hardly reap the same rewards. Justice, even in a make-believe world, eludes many. And the fairy tale can only have a happy ending if even the humblest person can participate in it.

All too often fairy stories can be about singular heroes, possessing superhuman strength, aided by predestiny, smashing their way through to a solution. But these are not lessons we can apply in our own, humdrum lives. What Goopy and Bagha show us is that even people most unlike fantasy heroes can save the day with nothing more than a caring heart and willing determination.

All Work And No Play

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, and its sequel, are pure fantasy films. They contain magic, ghosts, superpowers, and fictitious kingdoms going to war with each other. In other words, it is as far removed from the more typical Ray film as could be. Setting apart his family heritage, why would a director like Ray have shifted his sensibilities so far from what he was famous for?

This is actually a false dichotomy.

For a cerebral film-maker like Ray the importance of play would have held special relevance. It is a debilitation for any creative artist to be mired too long in the concerns of seriousness or commerce. To think only about sending a message or making money can make creative expression harder and harder, and diminish the chances of feeling joy in the act.

Therefore, the director of Aparajito also needs to make a Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne to balance his humours. To tell stories that are not bound by the logic and science of our own world is the very purpose of imagination and creative storytelling. One hero fighting off an army of villains is imaginary, no matter how realistic the visuals are or how well-trained the actor is.

Storytelling, the very essence of it, is to reduce life down to just the interesting parts. And reducing cinema to ‘what’s real is good and what’s unreal is bad’ is not the trait of any admirable film-maker. What is being made should be genuine only insofar as it comes from the heart, and no more. That is why a remarkable man like Ray could tackle such diverse styles and genres of stories without compromise or self-consciousness.

The aforementioned operatic sequence, popularly referred to as the Bhooter Naach, or The Dance of the Ghosts, is the most memorable example of this form of cinematic play. Our two protagonists, Goopy and Bagha, suddenly find themselves in the company of ghosts who introduce themselves by way of a long skit. Materialising out of thin air they go on to perform elaborate classical and modern dances accompanied by classical music and some cacophony. It is unexpected and long and feels like it’s in the middle of nowhere (literally and figuratively) and some viewers may even find it over-indulgent.

And that would be to miss the exact point. This is a film about indulging – indulging in the greatest exercises of wish-fulfilment. Ray is introducing a film within the film, or at least soldering together two disparate styles to form a wonderful creative whole. He doesn’t compromise on the running time he feels this sequence deserves just for the convenience of the audience that is used to more rapid cuts. At the same time he doesn’t belabour the action, and gives us genuine periods of enchantment, inviting us to drop our expectations and inhibitions. Breaking rules is not an accident, it’s the purpose.

After the Bhooter Naach, the king of the ghosts grants Goopy-Bagha special powers. They can teleport anywhere in the world, they can get any food anytime, they can be dressed in any fashion or disguise they desire, and they can mesmerise people with their music. In other words – food, fashion, travel, and star power. The life of a top-tier celebrity! Once again, that’s pure, unadulterated wish-fulfilment. The last one specially appeals to people of all ages – to be able to shut people up and get them out of your way.

Ray is inviting us to think like children, which is to be unbounded by concerns of pragmatism. He is freeing himself to break his rules and to explore facets of his own art and talents. I also feel he would have considered it his duty to make feature films for an under-served audience, namely children. In India the quality of content for children still remains poorer than it should be, and that also leads to large audiences of immature viewers for cinema overall.

Cinema is possibly the most powerful medium of imaginative storytelling because it can actually conjure up unreal things in the real world. The deceptive nature of special effects allows us to slide into the ‘suspension of disbelief’ phase and accept whatever’s on screen as real. Unfortunately that is a wasted tool when in the hands of film-makers who cannot conceive on an emotional scale and who play it safe by just offering thrills.

In the case of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, levitating pots of sweets are as real as the popcorn in your hands, and actually teleporting from deserts to glaciers is as believable as watching deserts and glaciers on the big screen.