UNDERSTANDING HUMANISM THROUGH THE FILMS OF SATYAJIT RAY

Ray and Ray

Let’s get this out of the way first –

No. I am not related to him.

Yes, I have often wished I was. It is magical to think of all the stories I could have heard about him to which no outsider would ever be privy. I envy people who would have watched him at work and at rest. Even to have been the quintessential fly on the wall would have made me a learned man today.

Of course, Satyajit Ray is not the only person of whose I wish I was a relative, friend or confidante. There are quite a lot of people really. But, Ray’s is the only instance where I have legitimately been asked that, for the obvious reason.

But, apart from that, there is a lot about his career that speaks to me directly as a viewer. He was a self-taught film-maker (I am a self-taught writer). His films reached heights of acclaim that no other Indian film-maker has (I do not think there is nobody else deserving, so all the more I wonder what made him destiny’s child). His films lack glamour and style and are yet replete with them. Images sing and music speaks in his works.

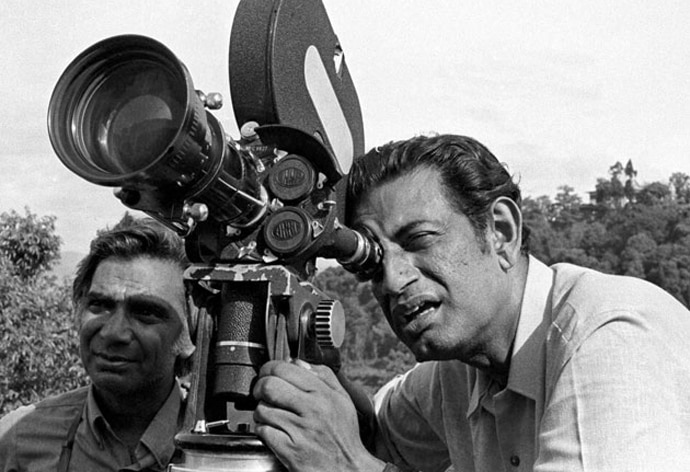

He was a director, screen-writer, music composer, graphic designer, all in one enormous six foot four package. Somebody could very well draw a cartoon of him as one of those street musicians with a guitar in his hand, a harmonica on a neck-brace, cymbals between his knees, and both feet on drum pedals, and that could neatly sum up his professional contributions.

I am hardly the first or last to notice his overwhelming talents or prodigious output. He has been celebrated by everyone from Akira Kurosawa to Martin Scorcese, Pauline Kael to Roger Ebert, the Academy Award committee, the Cannes committees, and the government of India through the Bharat Ratna. So what more can I say that hasn’t already been said before?

Since I am not a film maker, my approach to Ray’s films largely keeps away from shots, blocking, dollies and cranes. I am not a biographer who knows the stories behind the films or the director’s state of mind or stage of life during each project. There is nothing academic in my essays, nothing intersectional, post-modern, deconstructive, reconstructive, or any of those things, which I should know after studying literature, but unfortunately don’t. Any such qualities in my work are purely coincidental and not by design (but I’ll accept credit for it anyway).

What I have is a humanist approach to this greatest of all humanist filmmakers. Ray’s films, to me, were exemplary documents of the human condition, of the pressures piled on the individual and her response. There is nothing that stands out more in all his films than the conflict between the protagonist’s values and the screws turned on them by the powers that be.

What Would The Protagonist Do? That’s everything in his films. That’s everything that resonates with me. It came as a revelation, when it did, that a novel I had written was actually the perfect Satyajit Ray story. It was as if I had unconsciously written the next Calcutta Trilogy entry. It is a bond I cannot explain.

Of course, since I am mainly concerned with the nature of the story and what the storyteller wants us to know, I must mention here that most of Ray’s films are adaptations of works by other writers. But don’t think this is a limitation. Rather, it is an absolute thrill that Ray was as much a great film-maker as a great reader. That’s his secret recipe. Remember the cartoon I described a few paragraphs above? Where’s the need for that to also show him writing the songs? Cinema is a collaborative art so picking the right stories is as much an artistic talent as making the film.

A Man For All Seasons

Few film-makers have the kind of range that Ray exhibited through his career. The near-sighted viewer may associate him only with Pather Panchali, as most will, but it is truly dizzying to actually see the list of his films’ subjects. Try reading the following list in the voice of a waiter rattling off a long menu or a horse-race announcer:

- Man protagonist.

- Woman protagonist.

- Child protagonist.

- About the rich.

- About the poor.

- About the job-seeker.

- About the Managing Director.

- About the businessman.

- Fantasy films.

- Detective films.

- Adventure films.

- Realist films.

- Long form.

- Short form.

- Fiction films.

- Documentary films.

- Bengali language.

- Non-Bengali language.

People who create masterpieces don’t usually manage to spread out their talent so widely. It is almost a rule of the artistic pursuits that to be successful one must be known for doing one thing really well. The multi-faceted successful artist is really a unicorn. And yet there you have it. A prodigious output of 36 films (29 feature films, 2 short films, and 5 documentary films) across a career of 37 years (from the release of his first film in 1955 to his last one in 1992), and not including his parallel career as a writer of fiction (mainly for children) and non-fiction (mainly for cinema-lovers), contributor for other film-makers (as writer or music director), and a designer (for commercial clients before his film career, for his own films, and for various film groups et al). This is not a career that will let itself be forgotten easily.

Who Is The Bengali?

Sometimes I think of myself as a probashi Bengali, an émigré from my own mother culture. The reason I mention this is because when I work my way through the filmography of Ray, often accompanied by my wife (who considers herself an honorary Bengali), I find it educates, authenticates, and reaffirms a lot of what Bengali culture comprises of.

As I said before, Ray’s cinema is a cinema of humanism and the human is equally a product of their society even as they grapple with it. So the fate of his protagonists are often tied to their very Bengali values. After all, what one person considers a success may not match somebody else’s definition of it, and the same goes for definitions of compromise, of romance, of maturity. Can one even imagine what two unemployed youth would do with the excess of time on their hands without considering where they live and what access they have? Would ‘sneaking into a free film club to watch foreign films and for the free air-conditioning’ have been one of your considered options?

Ray’s films are quintessentially Bengali, and I can say that confidently even if I cannot define Bengali quintessence adequately. The joys, fears, and societal mores are all rooted in his culture (more often than not in the culture of the bhadralok), but he doesn’t make excuses for it either. A spade is a spade, a scoundrel is a scoundrel, a fraud is a fraud. No gloss of Bengali exceptionalism is called in to save the day.

That said, I cannot speak for the experience of non-Bengali viewers insofar as how this essentially Bengali storytelling comes across. But it is my belief that these films are parallelly local and universal and even if the viewer has to watch his films with subtitles, and may be occasionally lost without some kind of cultural guide to explain certain nuances, they will not find it to be fundamentally incompatible with their own experience.

Is Ray Relevant Today?

Thanks to the utter lack of film preservation in India, some of Ray’s films look like they were made before even the Lumiere Brothers. One can rightly wonder what place such outdated, scratchy, flickering films have in the modern day.

A much misused word is quite appropriate when applied to Ray’s cinema – timeless. The themes and nature of his cinema don’t age even though their idioms may have. Poverty, superstition, youthful angst – all of these exist in, perhaps, greater numbers than even during his lifetime. It is to the detriment of society that things today don’t look much better than during Ray’s early years.

Definitions of romance, of comedy, of action, of morality; these are always in flux. But what never changes is the fact that the individual always feels alone and in a fight against the world. That is where Ray’s films derive their validity. A BA degree may have been replaced by an MBA; a door-to-door sales job may now be a call-centre one; the children watching a train cut through the fields may now watch a movie on their father’s mobile phone of a drone delivering a parcel, but at the end of the day the look on their faces as they navigate the world they are born into seems to be the same across time.

He was also a remarkably generous film-maker, an opinion I base only on observations and not from any first-hand information. A pretty phenomenal number of actors, men and women, made their film debuts with him in central roles. I cannot imagine a greater calling than to be a wide-eyed newcomer being taken, by the hand, through the magical world of cinema, by the man who’s seen it all from the loftiest heights. Soumitra Chatterjee, his most frequent actor collaborator debuted with him. His crew, like Subrata Mitra (Cinematographer) and Bansi Chandragupta (Art Director) spent nearly the entirety of their career with him.

Moreover, Ray was also closely associated with film clubs even after hitting the big time himself. He designed logos and marketing material for these clubs and gave his time and reputation to help them grow. I cannot imagine any artist alive today who is so committed to nurturing the base of viewers/readers/listeners for their art like he was. Generosity and the willingness to mentor are forgotten qualities among today’s doyens, even those who once stood on the shoulders of giants themselves have forgotten to give back in the spirit of community that formed them.

The Silence of Satyajit

The remarkable ability of Ray, something that can only come from the utmost confidence in one’s craft, is that he leaves almost everything of importance unsaid. His films, his characters, don’t call attention to their most soaring and poignant moments. Where any other film-maker would have his characters narrate events of significance to others, Ray leaves it to us to narrate it to ourselves. His actors have to carry all the weight of communication on their faces, and then it is passed on to our analysing consciousness.

This may be the reason above all others why his films linger in our minds for days, or even years, like the words of the most profound teachers. To experience such life-affirming cinema, all you have to do to allow yourself to be truly, vulnerably human.

Methodology

As mentioned, my method is the absence of method. I have not consulted any books on his career to write these essays. Whatever I have read by him, or on him, has been many years in the past. My intent was to write as spontaneously and honestly as possible after viewing the films – to match the layperson’s experience. There is nothing academic here, just pure human response.

I have written these for people who have watched the films. Hence there is no attempt to summarise any of the plots. I would be adding no value by doing that. It’s meant to be like a discussion between two people, you and I, after a viewing.

There are spoilers for each film.

All images are used for the purpose of illustration (not commerce) and are, therefore, Fair Use. In case anybody owns the copyright for any of the images they may contact me and ask me to remove them.