THE GODSENT REMOVER OF OBSTACLES

After establishing the characters of Feluda, Jatayu, and Topshe with the first film in the series, Satyajit Ray would have been emboldened to inject the Feluda character with more personality and layers. [Of course, this is only true for the viewers of the films. Feluda as a literary series would already have plumbed much more depths in all the main characters already, and those who had read the books would have known the character with much greater familiarity.]

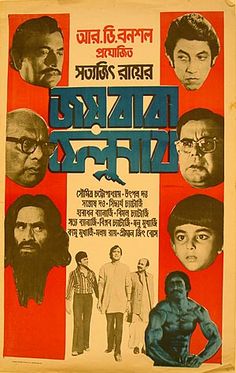

In many respects, Jai Baba Felunath is a much better film than Sonar Kella. The detective work in this film is much more serious, the dangers are as well. The locations are much more thrilling for the genre – narrow, twisting alleyways as opposed to wide, open, slow-moving spaces. Even the encounters with friends and foe help to develop the mystery in a much better manner. In my opinion, this film trumps both Sonar Kella and Chiriakhana in the detective genre.

Old Gods And New

The story takes place in the town of Benaras (also known as Varanasi and Kashi) which Ray had previously shown us inAparajito. As an ancient pilgrimage town it forms a fairly crackling setting for a theft and murder mystery. Throughout the film Ray keeps overlapping the human aspects of devotion and deception, like a thaumatrope spinning in the air.

In this ancient city of old gods, wealth and trickery stain the holy atmosphere. Just as there are many god-fearing and charitable people who come here for the spiritual vibes, it also attracts conmen and smugglers looking to make quick cash on valuable artifacts.

One such artifact is the stolen property – an idol of the god Ganesh, which is a family heirloom and also worth thousands of rupees to collectors. The prime suspect, Maganlal Meghraj, ia devotee of one Machchli Baba and makes annual pilgrimages to Benaras. On the surface, he is a god-fearing man himself, giving thanks for his prosperity through religious donations. And yet it is also common knowledge that he has been raided by the authorities on suspicion of smuggling away such idols, although no evidence was ever found.

This contradiction, between god-worship and money-worship, is the crux of the film. How can someone be so visibly pious, and yet so perceptibly crooked?

In many communities around the world, seeking well-being and seeking wealth have come to mean the same thing. While in the past it was considered appropriate for pious people to shun wealth and only pray for health and happiness, the gradual acceptance of wealth as a guarantor of health and happiness has made it possible for people to pray directly for wealth instead. To ask a god or goddess for money is no sacrilege because it is only with money that one can do good for others, or so at least is the common understanding.

Very symbolically, Ganesh is the ‘remover of obstacles’ and, not coincidentally, also a giver of wealth (wealth, after all, removes all obstacles). It can therefore be said that by stealing the idol of Ganesh, Maganlal has won him over to his side. If the authorities cannot catch him, then has he not received the blessing of Ganesh?

In contemporary literature there are writers and thinkers who have termed capitalism, media, technology et cetera as the new gods who rule the world. Wealth, surely is the only thing worthy of our devotion then. So when the family heirloom is converted to an object for sale, it signals the transition from the gods of old to the gods of new.

In this light, one returns to the question – how can a god-fearing person also be a criminal? By elevating the new gospel of personal prosperity to the forefront, that’s how. “Because god wanted me to have this, I have it. So it is not wrong because I am not punished.” Who can ever know the intent of god except through the success or failures of those who follow. If you suffer, god is unhappy with you. If you succeed, god is happy. If you’re hit with disease you’re in the bad books. If you win the lottery you’re in the good books.

In lieu of any other concrete evidence we have imposed our own understanding of loss and gain on to our gods. Material success has become the prime sign that you are on the right side of the old and new gods. After all, if kings rule by divine ordinance, then why can’t a citizen make a few extra bucks under the same authority?

Wolves In Sheep’s Clothing

But Ray, and by extension Feluda, don’t seem to agree. The film makes a case for disavowing those wolves in sheep’s clothing who distort spirituality and faith for the purpose of covering up their crimes. To misuse divine ordinance has been a practice for ages. Just consider witch and heretic burnings, caste atrocities, colonial oppression, warfare, and more. All of these have been ways of persecuting and exterminating millions of blameless people without facing any trial for crimes against humanity.

At the everyday level, many fake godmen have made fools of their devotees, giving faith a bad name. Even in a city held in such high regard conmen have their place to play. Before Feluda is tasked with catching the culprits, he was already in the city, drawn to it by its ancient energy. It is offensive to him, and many others, to have the city sullied by criminal activities. To catch a pious criminal is a service to the faithful.

The Machchli Baba, who has earned a large following among the hapless public, is revealed to be a fraud who masquerades as a holy man. In reality he is a conduit for the passage of stolen items, taking it off Maganlal’s hands in full sight of the same public, without arousing any suspicions. In a delicious twist, Feluda disguises himself as the Machchli Baba to deceive Maganlal, and catches him in the act of trying to pawn off the stolen Ganesh. Deceiving the deceiver by impersonating the impersonator.

When Feluda is finally about to capture Maganlal red-handed, he points the gun of divine retribution at him and says (I paraphrase), “Those who use money to harm others, cannot be saved by money.” He implies that money cannot remove all obstacles since greed for money is the obstacle.

This case is neatly tied up, but the thought does hover even afterwards – how many other Machchli Babas may be hiding in plain sight in every corner of the world, in every religion and denomination, using the public’s blind faith to rob them blind? How is it that so many of us have taken it for granted that putting all our hopes on man-made institutions of commerce is an acceptable form of devotion? By mixing faith with commerce and politics, have we not made the gods subservient to our institutions?

By unmasking one charlatan, Feluda encourages us to challenge all of the others.

Muscles Of The Mind And Body

Jai Baba Felunath is also a film that respects human skills. It positions religious devotion side-by-side with devotion to human potential. In many ways we are shown how pursuing excellence, in whichever chosen field, is a worthy way of life, and that devotion to self-improvement may be a higher purpose than devotion to gods.

The first man of talent we are introduced to is Bishwoshri, the body-builder. His mountainous physique is a sight to behold and nearly knocks Jatayu off his feet. Bishwoshri is not just a muscled maniac, but he treats his body like a precious work of art, and considers his physical regimen to be a matter of higher purpose. He philosophises about the dedication needed to achieve such peak fitness, and considers it no less worthy than earning a high college degree.

His exercise of the body is complementary to the mental musculature of our hero, Feluda. He and Bishwoshri are both at the peak of their respective fields (though, in keeping with the traditions of detective stories, Feluda is also very strong and fit himself) and they both know it takes constant practice to maintain their edge. To relax is to stagnate, so they are both continuously flexing their muscles.

However, at the thought of being in mortal danger, Bishwoshri is shown to be eager to pack up and flee. Even a man of enormous strength has to be afraid of a gun. He may have a rock-hard body but it is no bullet-proof. Feluda on the other hand is relatively unafraid and knows he can face the threat by being clever and alert. He realises that it is not the gun he is up against, but the person wielding it. And that person can be outwitted.

The other exhibitor of peerless skill is Arjun, the knife-thrower. At Maganlal’s house Arjun is asked to put on a display of his terrifying skills, using poor Jatayu as the target. Even though Arjun is a doddering old man with thick glasses and shaky hands, he is still able to command service from his weapons. His throw, his aim, are still perfect. After a lifetime of practice, it is as if his knives are directed by his mind rather than his body. He has achieved a confluence of mind and matter that even Feluda cannot match. What purpose Arjun uses that for is another matter.

The film seems to tells its younger viewers to take the practice of any skill very seriously, treat it with utmost devotion, and to go beyond mere repetition and competition. To be skilled in any field is a worthy achievement, though in a particularly Bengali manner, there seems to be a superior position for skills of the brain over those of brawn.

This is the last Feluda film made by Ray, and the last appearance of Soumitra Chatterjee as this character. Though the character has been revived many times by other directors and actors, the definitive image of the detective had been formed by these two films. Such affection for the detective exists among readers and viewers alike that till this day there is much devotion for Baba Felunath.