OUT, OUT, BRIEF CANDLE

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

– William Shakespeare, ‘Macbeth’

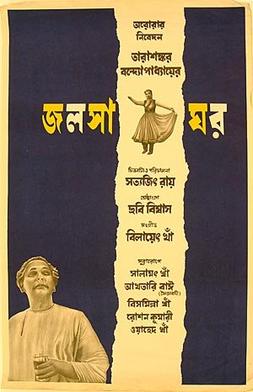

In Jalsaghar we are witness to one of the most isolated characters in all of Satyajit Ray’s films, Biswambhar Roy, standing alone in his fight against dusty death. He is a victim, a bully, a relic, and a king – in sum total, a man on the cusp of non-existence, facing death and ignominy. He wants to leave behind something for us to remember him by before it’s too late. But, maybe it was always too late for him.

Inheritance Of Loss

Biswambhar’s most obvious crisis is to grapple with the decline of his way of life. For this he cannot be blamed. He is a landed aristocrat, a feudal landlord whose way of life has existed for centuries. It’s not wrong to think that this is all that he and everyone around him knows. It’s as natural to him as roaming in the savannah is to a lion. There is no other way things can ever be.

And yet things are changing. Fast. In the nineteenth century, starting with western societies, the world started to decisively shift from a feudal system of existence to a capitalistic one. This meant the people who once had no power and no opportunity to rise above their birth station, could suddenly become aristocrats themselves, without land or dynasty. While it created hope for numerous masses, it was the death knell for those who were already at the top of the social pyramid.

Experiencing such tremors is Biswambhar. His income is dwindling as no longer is his ownership and control of land worth what it was. His tenants are moving to modern, industrialised sources of income, meaning they don’t need as much land as before. His credit with money-lenders is drying up, but he doesn’t cut down on what he thinks is a befitting lifestyle. As the local king, or its equivalent, he has to exist on a plane above all others, and this plane should not be linked to ordinary things like the absence of money.

Except that it very much is. Biswambhar is no longer living in his father’s world where money flowed in and out of their house like water. It has dried up, but yet the thirsty man continues to waste. And not only that, he is not teaching his son anything that can help him survive in his own time either. His son is taught to ride horses and sing – both undoubtedly noble pursuits, but ones that will not help him navigate the modern world.

At the heart of his dilemma is the fact that Biswambhar does not understand money, and hence cannot teach his son either. Whatever his ancestors did to amass wealth, they forgot to pass on the lessons to their children, and that’s why eventually this master of the mansion knows less about basic finance than his estate manager, or even his butler. He is spectacularly poised to fail because his plane of existence has separated too far from everybody else’s. It looks like Biswambhar is more surprised to learn that some young man from his region has made much money on his own merits, than he would be to suddenly find money materialising out of thin air in his vault.

He has never been taught how to live like a human being, instead he believes he is divinely ordained. Even when there is no work for him, he still chooses to stay back when his wife and son take a trip. He believes his presence is required on his estate, although even his wife laughs at his delusion. Later, when his wife and child die on their journey, he is left without any family. Instead of believing in his relevance, which doesn’t exist, he could have saved them or at least died together.

These are strange choices, no doubt, and one cannot say that the rest of us would have made the transition smoothly. After all we are a species that repeatedly squirms away from change at even the basic phases of life: like living independently, having children move away, marrying, and dying. These are such common and welcome parts of our lives and yet each of us faces them like crises.

Yet, this is the difference between him and the rest of us. He wouldn’t have resisted any of these transitions because for him they are rituals. As king he has to present himself in a certain way and that includes taking a high-bred wife and producing a prince. And as long as money is no object, each act of these rituals can be performed with grandeur that is its own purpose. His son’s thread ceremony has to be done with pomp, because spending is the objective. Being economical is not just unthinkable, it’s tantamount to invoking a curse.

Biswambhar does not realise he is being impractical because his upbringing taught him these were the right steps to take. After all, there was a time when hunting tigers was a way to show your manliness. But, when there are no more tigers left to hunt, what is the substitute?

The Show Must Go On

The Jalsaghar, basically the same as a ballroom in western cultures, is a world within a world. Inside this room, none of Biswambhar’s problems seem to exist. Wine continues to flow, music never stops, in fact the sound of ghungroos gets even louder during the toughest of times. There is even a lovely looking glass where he can admire himself. Along the walls, his ancestors wax aristocratic at him from paintings. This room is Biswambhar’s drug, his escape route.

While he leads the audience in enjoyment, the ones who really give life to this room are the various musicians he invites to perform. These singers, instrumentalists, and dancers, are par excellence. They can drive their audience to ecstasy and then lull their senses like alcohol.

Interestingly, these musicians could have given Biswambhar a masterclass in adaptation. Like him, they faced many upheavals in their profession, and their way of life changed forms but survived all the way till present times, much longer than he will.

Classical musicians had depended on royal and noble patronage to earn their fees. Whether performing for the king’s courts, or aristocrats, they needed patrons to pay them handsomely for private performances. Their kind of music couldn’t have been performed in large public spaces, nor would their years of practice have been sufficiently funded by meagre ticket sales.

When the age of kings ended with the coming of the British (something one can see in Ray’s other film Shatranj Ke Khiladi) these musicians had to come to terms with the changes. Firstly, they relocated away from traditional seats of power to the new centres. Biswambhar himself was benefitting from this migration, as many of his invited artistes may originally have belonged to cities like Lucknow and Delhi, and not Calcutta or anywhere near his village of Kirtipur. These musicians realised they could not be rooted to their respective spots, even though that’s what many of their previous patrons may have done.

Having moved, the musicians also knew they needed to find the new wealthy people they could tap for money. Even they may have felt the prick of performing for uncultured people after having once been invitees of Maharajas, and yet to survive they did what they must. And what they did also kept their musical traditions alive, which was certainly because of their dedication. They didn’t passively allow generations of skill die out. What could have been the funeral of their way of life became a chance to think and regroup stronger.

An even bigger crisis faced by musicians, though not part of this film’s narrative, was the advent of audio recordings. Many musicians had felt outraged by the thought that their work could be sold as inert recordings. But those who resisted, whom I will not blame, also lost the game over time to those who embraced the new technology. Recordings immortalised many, even as their teachers and predecessors have been forgotten.

Biswambhar would have done well to look at the survival instincts of these artistes as then he could have negotiated with the new world as well. If land was no longer yielding returns, he might have tried doing what others did and adopt modern businesses. He didn’t have to do it alone either, his manager was ever willing to do it for him. All Biswambhar needed to do was give him the green signal. But in reality all he did was to throw another expensive party.

The Man In The Mirror

Almost every scene in the film abounds (maybe a little too much) with the symbolism of decay and demise. Water leaks from the ceiling during a storm. A frog swims in a glass of alcohol. An old elephant gets hidden in the dust kicked up by a truck. Riding a horse named Toofan (‘storm’) Biswambhar falls to his death. And when he dies, his dynastic, kingly blood spills out on the dry earth.

But the one that stands out, from the very first frame, is the chandelier. This chandelier, like all the grand ones of its time, is lit by candles. It has pride of place and is like a jewel for the house itself. Every time it is lit it means there will be a celebration.

After the final music night, Biswambhar is steeped in alcohol and admires the chandeliers. But suddenly, as he is up late, he starts to see the candles go out one by one (the last one awake will naturally be the one to see the candles die). He doesn’t want them to as he doesn’t want to be in darkness. He doesn’t want the night to end.

But how can he stop it? All days give way to night, and then again nights give way to day. Candles go out and other candles take their place. To try and extend a lit candle’s life indefinitely is to try and change nature itself.

If one wants lights that can stay on all night, it has to be electric. Those perform better in the modern age. Soon the other houses will get them, but Biswambhar probably wouldn’t have. If he wants the light to stay on all night, he needs to move with the times. If he wants his old ways, he has to be content to be side-lined. He cannot have it both ways, no matter how much he rages.

When Biswambhar looks at his visage in the mirror he is shocked by how much he’s aged. It would have been accelerated by the sorrow of losing his wife and son. But a man who doesn’t know how much he’s changed, because he doesn’t look in the mirror, is a man who will be surprised by any and every change. He has not accepted that time will change everything. Just because his ancestral way of life seemed eternal doesn’t mean it was. A ship that doesn’t get retired timely must go down sometime. And somebody will be the captain at that time who will also go down with it. It is Biswambhar’s tragedy that that captain is him. But it’s not personal. Time hasn’t singled him out. If it wasn’t him it would have befallen his son, and would that have made him feel any better?

But where he fails is to fade away gracefully. The blood in his veins, that he’s so proud of, has not taught him to accept ageing with equanimity. Perhaps he was hoping he can make way for the rise of his son and that’s what he had prepared for. Being alone, without the presence of grandchildren to help him transition into the role of old man, he is lost. But when he mounts his horse and rides at a furious pace till he is thrown and dies, he displays behaviour more suited to a modern rock-star who lives life hard and fast and refuses to spend a moment being ordinary.

All of us will face the prospects of becomes redundant in this giant world of ours. Not only us as individuals, but our way of life, our culture, our networks, every will change. In fact, the pace of change is such now that each generation will face what Biswambhar was facing once-in-generations. Are we all to react to it the way he did? We many not realise it, but many of us do. We rage and rant in our old age, unwilling to accept that things that mattered to us, no longer matter to others. And maybe they should, maybe we believed in good things. But change is not personal.

So what could Biswambhar have done? Maybe he needed more companions in life. He could have adopted children or re-married. His attendants were loyal, he could have listened to them more. When new businesses made their appearance on his estate he could have tried to understand how they work. That could have delayed the extinguishing of the candles. Or he could have used his remaining money to do some good for his people and watched them enjoy the fruits of his generosity.

Some of his loss was just misfortune, some of it was his own fault. His age-old way of life taught him to enjoy the good things while it lasted but not how to face decline. This lesson needs to be taught to us all. If we take the time to understand what brings us happiness in our advanced years the celebration room can be repurposed.