WORKING LIFE OF THE WORKING WIFE

One of the most prevalent themes in the filmography of Satyajit Ray, if not the most prevalent theme, is work and its effect on the individual. So many of his films interrogate this directly or indirectly that it feels like watching people at work was an addiction for him. Right from Apur Sansar we see his characters try to find jobs, keep jobs, make ends meet for their family, leave jobs, scorn jobs, and even (nearly) murder for their jobs.

There was no end to Ray’s fascination with this theme, and perhaps this could be explained by the Marxist/communist ethos of the city and culture where he operated. Ray’s own family members were well-off writers, artists, and publishers. This could be why he was able to take an outsider’s view to the whole qualification-application-promotion process. Moreover, the humanist in him was acutely aware of the ways in which work could lobotomise much of the essence of individuals and distort them into numb, or sometimes terrifying, versions of themselves.

However, the first of his films to directly deal with the world of employment is actually the sweetest and most heart-warming in tone, and progressively the latter instalments become more bleak and irredeemable.

[A clarification is appropriate here. People commonly club three of Ray’s films together and call it the Calcutta Trilogy: Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya. It is not clear to me what this classification achieves. These are not the only films set in Calcutta. Starting with parts of the Apu Trilogy, then Parash Pathar, and all the way up to Agantuk, many of his other films use Calcutta as a setting. Neither can we say that the Calcutta Trilogy is Ray’s exclusive take on the working life, because then Mahanagar becomes a glaring omission, especially since it pre-dates the rest by a full seven years.

It seems to be just the over-enthusiasm of people to classify works of art in a trilogy that led to this faulty grouping, or just to throw it into a ring with Mrinal Sen’s Calcutta Trilogy and have them battle for our pleasure.

Either way, this so-called ‘Calcutta Trilogy’ term should be discarded, and if needs must then I propose the accurate alternative – The Rojgar Quartet (rojgar being the Bengali word for livelihood) comprising of Mahanagar, Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya.]

Work And The Wider World

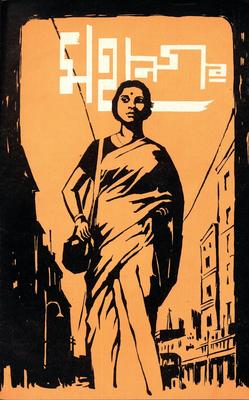

The dutiful housewife Aarati, played to perfection by Madhabi Mukherjee, knows her duties inside-out. She takes care of the children, the in-laws, and the husband. There is always a smile on her face, never a harsh word, and she keeps all the plates spinning in a frenetic show of housewife-ly virtuosity.

Things are all well and good until the list of people’s unmet needs seems to start growing, particularly when her father-in-law needs new spectacles. The household budget is stretched so thin that there is not enough in reserve funds to fulfil this critical purchase. Is her husband, Subrata’s, salary ever going to be enough, especially with a growing son and soon-to-be marriageable sister-in-law around?

While the thought never seems to occur to any other member of the family, it comes as an obvious answer to Aarati – she needs to get a job. Bam! Right off the bat we see the Ray heroine take charge and cut through the flab of domestic role-play. We know she likes to skip cooking once-in-a-while, and likes to be a playful elder rather than a stern one. So it’s not necessary that she beat around the bush to get to the point. Money not enough; ergo more money needed; hence second income mandatory. Quite simple.

And yet, it is in the choice to do away with the dramatics that we can establish her whole character – direct, pragmatic, and up to a challenge.

It almost makes one wonder what exactly might be the cause for hesitation in others, including the family members. What about such an obvious necessity is still resisted, passively and actively, by her husband, in-laws, and her own father. Her only cheerleader at home is the young sister-in-law.

The outside world (anything outside the house) has always been seen as no-woman’s land in many cultures. Among Asian cultures this is taken so far as to cover the woman’s body, right up to her face, and refuse to have her spend time with, or even be visible to non-husband, non-child male!

Even if we like to think that in modern times we no longer think of women as property, we still don’t like them having control over their own life. Any work outside the home is an arena of making independent choices daily and engaging in non-domestic interactions. Simply forget about it.

But what happens to Subrata and Aarati is something that happened to families the world over in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – the income of a single, salaried, landless, city-dwelling man just didn’t stretch far enough to support the two (couple) plus two (children) plus two (parents) plus God-knows-how-many-more family unit. This could only lead in the direction of nuclear families, and the miracle of miracles that is the earning woman.

Of course, Aarati’s father-in-law still cannot reconcile himself to such a scurrilous notion, literally and figuratively choosing blindness over acceptance. It is no noble tradition that he clasps himself to, no matter how benevolent he might seem. He is more than ready to beg favours from outsiders and even becomes something of a Munchausen in selling his sorrows to gain sympathy from strangers. Such was the dogged determination in many to reject the advent of the working woman.

Once she has her chance, Aarati doesn’t look back. Despite a few initial hiccups, she gets into the flow of her work like she was to the manor born. Such is her progress that the manager singles her out for fast-tracking. Her behaviour is most directly depicted in her changed dressing. She wears more fashionable clothes, is taught how to use lip-stick by her colleague, walks confidently to clients’ homes, and even meets male friends over lunch while angling for jobs for her husband.

This is what happens when a woman decides to, is allowed to, work. She becomes worldly, she becomes tactical, she makes plans, she makes choices. And this is what the fear has always been about.

Change And The Male Ego

Whether this new-found confidence is a source of pride, jealousy, or insecurity in Subrata should not come as a surprise. It doesn’t help his situation that he loses his own job mid-way through the film and he is left entirely dependent on his wife. This means he has to choose between actually being penniless or letting his wife take charge. His worst fears are realised, but shouldn’t this be his fondest dream – of having a wife who is an equal partner in their marriage?

But Subrata is not a villain and Ray had taken care to soften his character compared to the same character in the original short story by Narendranath Mitra. Lesser film-makers would prefer the clear-cut good-bad or hero-villain duality. Ray wants greys.

For centuries the male ego has trained itself to think that love and respect are only around so long as the man is useful. In other words, be the bread-winner, the earner, the man of the house, or else your wife and children will trade you in for another model. It is the counterpart to women’s issues of beauty. In the wild, a male that cannot hunt (like a woman that cannot breed) is soon going to fall behind and die, so also will the human male.

But humans are not the same kind of animals. We have always been social and nurturing. It has been our tendency since prehistory to take care of dependents. So why should the male, especially an urban, salaried male (the farthest thing from a beast of the savannah) still measure self-worth in the same manner?

One of the scenes that pinches Subrata, and possibly every male viewer of the film, is when his wife has lunch with another man. This person is actually a friend of Subrata’s who Aarati happens to bump into and share a meal with. Apart from the usual niceties she brings up the question of finding her husband a job. Why does this scene hit us so hard? Apart from the churlishness brought about by the thought of one’s wife being friends with any other man, this man is ostensibly more successful and has a certain flair in his mannerisms which mark him exactly as the kind of male competitor that Subrata fears he could lose out to.

Earning has become the biggest indicator of masculinity in our society, replacing the older and equally stunted criteria of physical strength. The needs of modern families have changed and so ought to the measure of strength and utility. Anyone can pay the bills, not everyone can wipe away tears. Subrata is caught between being the man he wants to be and the man he is expected to be.

His own father, happily dependent on his wife and son, cannot imagine accepting his spectacles from the daughter-in-law’s earnings. And though he isn’t an ogrish figure, in fact he is quite soft and gentle, he can still manage to emasculate his own son by talking about how he never needed to send his own wife out to work. These are deeply ingrained systems of value and even the most outwardly enlightened and liberal men can have the same insecurities. The father even betrays his son by seeking favours from his former students to the extent that it makes Subrata appear to be neglectful. Fortunately, the unfairness of the situation eventually dawns on him and he indicates his willingness to change.

The way to rescue oneself from such inhibitors, as it seems to me, is to trust your partner. If there is no reason to believe they will abandon you if the direction of the wind changes in your life, then trust them to do the right thing. Jealousy and envy are terrible termites in any relationship and the couple must face the world together. In the interest of peace and common good, like in Presidential elections, it is necessary to have a peaceful transition of power.

The last scene of the film shows the couple disappearing into a crowd and the camera pans to settle on a streetlight. On close observation we see one working bulb and two other empty sockets. Ray seems to be telling us that as long as one bulb is plugged in there will be light.

Colleagues and Compassion

Apart from the husband-wife relationship, the next most explored relationship in the film is the working woman and her colleague Edith. Edith is an Anglo-Indian woman who speaks primarily in English and wears western clothes. She is also not temperamentally docile like many others and can go so far as to demand monetary incentives for herself and the team.

In other words – she is a code-red disaster for the Bengali male management embodied in the person of Mukherjee. Mukherjee is the typical modern smooth-talking manager, someone who likes to be friendly and approachable right until his authority is questioned. He’s a friend who doesn’t tolerate insubordination. And, in the slick style of many managers, he is happy to promote a person he feels is more pliable and willing to act as his agent, and fire the person who rubbed him the wrong way.

At first he takes pains to show how respectful he is of his female employees and their capabilities. After all, why would he hire them if he wasn’t a supporter of working women? And yet, this progressive operation may only be due to the fact that they are a manufacturer of knitting machines and similar products targeted at domestic women. Having women on the work force may be good business, not good humanity.

The suspicion of this is planted when the women find out they are not being given commissions on sales like employees of rival companies. Demanding this right, led from the front by Edith, becomes a warning sign for Mukherjee. From that moment on we can assume he is out to sever the head of the uprising, that is to say he is looking for an excuse to fire Edith. And he finds his excuses soon enough.

A period of absence from work due to illness is manufactured into a lie that she is an irresponsible woman of dubious character who is nobody’s friend. Not only must she be removed, she also must be maligned in front of the others so they feel no attachment to her. Divide-and-rule is not just a colonial weapon.

The question facing Aarati under these circumstances, as would be familiar to nearly everyone reading this, is whether to take a stand in solidarity and risk their own jobs for their principles, or whether to accept the system’s power and fall in line to protect the well-being of one’s own family. No one can be blamed if their chose the path of lesser resistance.

Aarati does not. She quits in outrage over the treatment of her friend, especially since she is an eyewitness to the truth of Edith’s defence. She is not a slave yet, and maybe she doesn’t have the calculating logic to see the bigger picture. But she has belief in her principles and in human dignity. She cannot throw away a friend just because it is more profitable to do so. One wonders if this is the power of working women that can truly shake the workplace.

It is a funny dichotomy. On the one hand we all probably feel she made a foolhardy choice that benefits no one and creates two jobless women instead of one. But on the other hand, which of us has not considered striking such a symbolic blow to the system that doesn’t even realise when it robs individuals of their dignity. We pity and envy Aarati simultaneously.

So are loyalty and compassion specifically female traits? Of course not. But society has been assigning genders to human traits for so long that we have been brainwashed into thinking so. If we could all have the courage to act like Aarati, then the system would work better for everyone. If Mukherjee had the humility to listen, then he wouldn’t have lost his star employee. Both partners need each other to form a stable relationship, whether it is a wife and husband partnership, or employee-employer. It is only through the cracks in a relationship that we allow others to invade and overthrow us.