CAN THE CAGED BIRD SING?

It is a tragicomedy of our lives that just as we start to get a sense of who we are as individuals, it is right then that we are also compelled to shed our identity and amalgamate with society at large.

As children we are the centre of the universe and our joys and sorrows are treated as the be-all-and-end-all of our family’s existence. As youth and fledgling adults we understand our core values better, form opinions, and consider which path we would like to spend our lives on.

And then what happens? We need to look for jobs, we need to train for jobs, and livelihood becomes the centre of our lives. Whether you are an engineer or a farmer, a working woman or a home-maker, you need to work. Whereas some people live to eat while others eat to live, with work it all takes one approach – live to work.

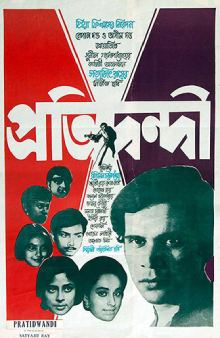

In Satyajit Ray’s Rojgari Quartet (my coinage) Pratidwandi is the film that looks at the working man looking to start his career, the time when the inner conflict is at its highest.

Qualification And Individuality

In older times getting work could happen in either of two ways. First, you know somebody has a need for an employee so you present yourself as willing and able-bodied. Thereafter, you are taken under the employers tutelage and learn the ropes, hoping that one day you will have your own trade. The second way was to follow in the family trade. Offspring of a farmer becomes a farmer, offspring of a potter becomes a potter, offspring of a priest (like in the Apu Trilogy) becomes a priest.

While it is true that there was not much choice or free will exercised in finding such jobs, there was also not much by way of expectation. After the industrial revolution and the beginning of a new class of jobs, such as services and artists, expectations of what comprised a good life changed.

Coming to the twentieth century one suddenly had a whole horde of professions that had no presence even fifty years ago. One could dream of being a journalist, a radio musician, a film-maker, an archaeologist, a sociologist, and so on. Even professions that existed for centuries prior, like musician or writer, took on a whole new form and feasibility. How could a budding young woman or man decide which was right for them?

On the other hand were the employers. With so many people to choose from, and higher stakes in their business, they wanted to be sure the people they were hiring were the most well-suited to employ. Gone were the days of apprentices giving ten-fifteen years to one master from whom they learned everything and to whom they gave everything. An unsatisfied employee could leave in a matter of months leaving the position open once again.

In a volatile situation what counts as qualification to undertake a certain kind of work? Enter the generalised qualification tests and criteria. Start hiring people with degrees targeted towards a single profession – whether engineering or accountancy, sales or education, a qualification for everything was available and requisite. No employer needed to waste time on an arts graduate candidate for an architect’s job. Given time anybody could prove their value in a role if they worked hard, but time was always scarce.

When even these restrictions weren’t enough, start interviewing candidates even after they show their degrees, or conduct your own tests, or ask for recommendations, or prior experience, and so on. With thousands of applicants and hundreds of vacancies, the process of selection inevitably morphed into a process of elimination. What you had didn’t matter as much as what you didn’t have.

Siddhartha, played by the suave debutant Dhritiman Chatterjee, is such a young man who faces rejection over and over again despite having all requisites for getting a desirable job. He completed half an honours degree in medicine before having to give it up when his father died. He is very well-spoken, carries himself well, is informed on global events, and also needs to be the steady earning member of his family.

What then prevents a person like him, with the benefits of education and the necessity to be a productive member of society, from landing a commensurate role? The fact that there are thousands of others with the same qualification, and who didn’t have to drop out of their degree mid-way either. In simple economic terms: it is a demand-and-supply issue where it is a buyer’s market. Remarkably, even half-a-century later things haven’t improved in the country.

So, is there anything in the hands of the candidate anymore? When exigencies of life take you out of the formal route, then are you to be discarded by the roadside like litter? There are only two paths left to the repeatedly rejected candidate. One is to find a way to jump the queue. This could be in the form of finding someone influential to advocate for you, or by faking your qualifications, or even by compromising on your morals by offering bribes or sexual favours. In a buyer’s market you are forced to offer deals and bundled goodies with yourself.

An acquaintance of Siddharth is a well-connected political agent who happens to know someone willing to give him a job. Through this contact Siddharth has the option of jumping the queue, and that too without compromising on his morals. The only drawback is that the job is somewhat lowly compared to his qualifications. What choices do beggars have?

The other path for the rejected candidate is a descension into rage. It is a rejection of all optimism, of all hopes for a better future, all belief in fair treatment and turn into a ball of white-hot rage that only wants to burn society down. This rage may be a threat to authorities, and even declared illegal, but it is the natural human response to a system that doesn’t not care an iota for them. If human life is reduced to the status of an inanimate object, then that object may as well be a cannonball hurling itself at the high walls of society.

Crossing which line can turn an ordinary man or woman into an adversary of society?

(Bird) Songs Of Innocence And Experience

Siddharth is a man trying hard to settle his present while being incessantly haunted by the past. The tussle between his dreams and his pragmatism in contained in a recurring past vs present battle in his mind.

Siddharth keeps lapsing into reminiscences of his past. The nearer memories are from his days studying medicine, particularly his lectures. Like a Proust character, things Siddharth encounters while walking on the streets can trigger these memories. It is almost as if despite everything he has learnt in all his years of education, he has found no explanation for his current woes. If only there were lessons for that as well, simple answers to direct questions, then he would not be so lost in his present. Alas all the hours of lectures couldn’t get him a botanist’s job, and plants are far easier to understand than humans.

The other reminiscences he has are of a family picnic from his childhood where he and his younger sister and younger brother had explored some woods. Not only are these obvious symbols of a happier and more innocent past self, they also serve to show us just how far we change as human beings under social and economic forces.

All three children are a unit in the dreams, exploring a lake and the surrounding trees when one of them hears a unique bird-song. She calls out to Siddharth and he too can hear it, though none of them can see the bird. Almost like a fairy tale Siddharth’s brain has bottled up that bird-song as the most special souvenir from that picnic. His brain occasionally releases it like dopamine, a way to calm himself during turbulent moments, and makes him a different kind of seeker – not one seeking a job, but seeking a state of mind.

Even though like all siblings they were shaped by the same background and history, all three have grown up along different paths. Siddharth, the eldest, has been more paternal, a father-figure, and tries to take the role of patriarch even if that’s not what he actually wants. The middle child, his sister, is the only one who is employed, and is navigating the line between income and compromise. Rumours reach home about her dalliances with her manager, and when confronted she doesn’t care to deny or confirm them. She is the pragmatist Siddharth can never be.

The youngest sibling is still in college but deeply involved with the communist and Naxal movements. He has taken the path of revolution, of resistance, and despite being the youngest he has chosen the hardest life. He even gives Siddharth a lesson on principles that are worth fighting for. Siddharth may try to give his younger brother advice but his life has not only stagnated, but he also does not seem to have the range of life experience that his brother has. He is the rebel that Siddharth can never be.

By comparison to his siblings Siddharth comes across as the only one who hasn’t picked a side and still seems to numbly knock on doors that are forever closed to him. Both the siblings react to changing situations, Siddharth remains inert. But for how long?

He has a dream one night, where he sees his sister as a fashion model, something he views as cheap work, while his brother is standing in front of a firing squad ready for execution. Siddharth can do nothing for them because somewhere in all this a job interview panel is awaiting him. He sees a nurse run to his brother’s corpse, who could be a prostitute his friend had taken him to one time, and this prostitute also becomes his own sister. Finally his dream shows him the woman he recently met, someone he can actually speak to and who rescues him from his wild dream like a bird-song.

While Siddharth never saw the bird singing the song, he does remember another incident where he and his brother watched a chicken being slaughtered. He can’t stomach the scene though his brother watched the entire execution. In the present time Siddharth goes to a bird market with his friend hoping he can find one of those sweet singing birds for his home – possibly a desperate search for a talisman. But in the cacophony of hundreds of shrieking birds he cannot hear any melody. Even when asked to whistle the song so the shop-owner can try and identify the bird, Siddharth is unable to produce any sound. In all this cacophony can any bird sing?

City Lights, City Sounds

The cacophony is the city. The city is Calcutta. The birds are all the lost souls akin to Siddharth.

The figure of the nurse-prostitute stands out starkly. Nursing is the noblest of professions, and yet this woman needs to prostitute herself to make ends meet. In both ways she is giving of herself, but neither way is she getting any respect for herself. Where is the light in a city if this is what it forces someone to do for a living.

An ever-growing populace in an ever-degrading city is the story of every major urban centre of the world. As beacons of hope it attracts people from far and wide with the promise of jobs and food and shelter. Yet, even when these run out the people keep coming, and coming, until living conditions become pathetic and hope clings on to dying embers. The promise has become a mirage, but no one seems to be able to tell the difference.

Young people like Siddharth who have spent all their lives in the city have come to depend on it for more than just jobs. After all the identity they have formed takes all its elements from the melting pot. Their colleges, restaurants, markets, film clubs, everything is here, not to mention all their friends. Just as hard it was for people from the countryside to leave everything and move to the city, so it is for the city-dwellers to move away.

He and his friends say as much. They cannot leave, they don’t want to leave. Jobs are meant to facilitate their staying on and not the reverse. The ready job that was offered to Siddharth requires him to leave Calcutta, which he is not ready to do. And yet the city he loves so much does not love him back.

One day Siddharth visits his sister’s manager with the intention of intimidating him for taking advantage of his sister. But, sitting in that man’s spacious house he realises his lower status and loses his nerve. Later on the street he sees a car accident take place and an angry mob beating the car’s driver. Having just faced a humiliating personal defeat he lets his rage loose and tries to join the mob in beating the driver of the Mercedes-Benz. But even here, like in all the job interviews, there are too many takers and he cannot make it through the crowd. He then sees a school-going girl in her car watching the violence with a look of utter fear. Siddharth is silently ashamed at what he was about to take part in. He was ready to do something that would shock a child. He has been reduced to acting like a thug just to vent some of his frustration.

But that frustration doesn’t just go away. It builds and builds until his ego cannot take any more lashings. The last interview he attempts has more candidates than he has ever seen and they are all made to wait in the balcony corridors without sufficient ceiling fans, seats, or shade from the sun. When the candidates ask for some extra chairs they are threatened with exclusion from the entry process. Siddharth’s anger grows and explodes in righteous fury and he barges into the interview room and bashes up the literal and figurative gate-keepers.

The cannonball has hurled itself. But can it also pick itself up after that and learn to be anything other than ammunition?

The process just wouldn’t work for someone like him no matter how much he waited for his turn and finally he accepts that. He has to take the job outside the city because that’s the only way to take his life back. There is also an indication that he may have found a life partner in the woman he had met earlier in the film which brings another source of hope for him.

In a stark situation as this, there is hope only if we make great sacrifices. Tragically, even when we are prepared to give, we may be asked to give more. But unless one is a rebel warrior, there is no fighting the system except by taking what’s on offer and finding a way to make that work.

When he is away from the throng, away from the gears that squeezed him, away from the cacophony, once again Siddharth can hear the bird-song. Only, this time it’s for real.