THUS FAR, AND NO FARTHER

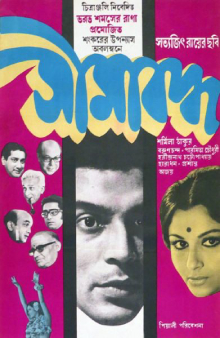

After dealing with the reasons for taking up a job (in Mahanagar), and the difficulties of getting a job (in Pratidwandi), Satyajit Ray’s next instalment of the Rojgari Quartet (my coinage) picks up the theme of job advancement.

Right off the bat, Seemabaddha spells out how it carries on from, and differs from, Pratidwandi when the protagonist mentions how he is not one of the horde of helpless job-seekers. Maybe, like him, one gets lucky and has a smooth entry into the working life than most others, but is that a guarantee of smooth sailing thereafter? Well begun may be half done, but the other half still looms.

In that case, like the Company Limited (a type of company incorporation) even the employee is limited. But whereas for the company it means its liability is limited, in the employee’s situation it is his liberty that is limited.

Middle Class Mobility

Social mobility is a relatively recent phenomenon in human society. For many centuries, it wasn’t possible to move from one class to another no matter what dreams one may have. Wealth could come and go, but it would still take a terrific turn of fate, like being picked to marry a king, or suffering some horrific disease, that could knock one up or down.

But with the weakening of monarchies, the rise of the cities, and the invention of many service or knowledge-oriented jobs, slowly and surely a lot of the class divisions became blurred. It became possible for people to improve their standing by a few notches within half-a-lifetime. Capitalists replaced the landowners in the role of wealth-generators, democracies replaced theocracies, and educated young men (not yet women) of good social standing (unfortunately caste and race still mattered) could live lives of unprecedented poshness.

The middle class, more than the lower or upper, could take advantage of these opportunities. The lower still remained mired in many disadvantages that weren’t easy to shake-off, and the upper clutched on to its position with desperation and cunning.

It is such an upwardly-mobile man we meet in the form of Shyamal. When Shyamal learns that his wife’s younger sister, Tutul, is coming for a visit he is thrilled at the prospect of showing-off to an ingenue. He puts on his most effortlessly cool airs, showing her the sights and sounds of the Calcutta he inhabits – of large office cabins and conference rooms, fast cars, race tracks and clubs with swimming pools, of swank company flats, and indolent parties. He instructs his wife in how to dress her sister up for an evening with his colleagues. His colleagues display the brashness of their corporate positions by proclaiming loud and obnoxious opinions on other people, while Shyamal silently indulges them.

He is a man on the rise, in line for a big promotion as Sales Manager for a large electrical manufacturing company. He handles sales for fans, and his office rival does the same for lights. One of them will be elevated to the position of Director, and receive the attendant privileges that go with it, namely bigger house, bigger car, fatter salary, access to the boardroom, and so on.

Shyamal has every reason to be proud of his achievements. He comes from an ordinary family where his father had been a teacher, as also his father-in-law. He started as a teacher himself before answering a recruitment offer from his present company and finding that all his capabilities had a significant rupee-value, more than anybody in his family ever knew. Thus he is the first to break away from his hereditary role.

The arrival of Tutul allows him to put on the grand tour, something he must have done for others as well, but which has an especial appeal now. After all, parents are still expected to be conservative, children aren’t easily impressed, but a young sister-in-law would appreciate it all and hero-worship such a lofty male figure. He can put on a suave and sophisticated air, smoke and drink and play music, speak like an intellectual, and drive like an adrenaline-junkie, all in service to an image. Even the view from their high-rise flat is an embellishment with the commanding view that nobody walking on the street can ever enjoy. Upward mobility made literal.

Easy Entry, Impossible Exit

A Faustian bargain sounds like it only exists in stories about the most powerful people. You strike a deal to become the highest-selling author, or the richest oil tycoon, or a President. After all, unless one is trying to become a billionaire or a world leader, what possible use could the devil have in your mundane soul? Sales Manager hardly seems like the kind of role for which you’ll not even hand over your car keys, let alone your very soul.

And yet, quite possibly millions of people make this bargain, renew the terms every day, and don’t even realise that they are doing so. It is all covered up by the blanket acceptance of compromise, pragmatism, and ‘looking out for oneself’.

After all, you can blissfully work for fossil fuel companies, pesticide companies, opioid companies, data gathering companies, twisted media companies, blood diamond companies, adulterated food companies, and on and on and on, without ever considering your part in perpetuating a pox on society. It would be easier to list industries that aren’t tainted by some form of corruption or the other, because there are none.

So what then is an earnest employee, looking to do the best by themself and their family to do? One cannot remain unemployed just to stick it to an unfair system. If you’re stranded at sea, you must drink sea water.

In that small act of choosing to overlook the evils of corporations, and of denying responsibility, we may strike such a bargain with the devil. We look the other way, and in return we get to keep a bubble of blissful ignorance. In the long term, especially if we are believers in concepts like hell and rebirth, we accept we may be paying a price. But today our prospects are bright.

[The joke’s on the devil, though. The hunt for the soul is a thrill only when it is rare. But when immense numbers of people are throwing themselves into compromise in return for material rewards, it is the devil who finds himself at sea. The devil has no place anymore to keep the souls of all the people who have done cruel and selfish things just for a promotion.]

And what is a promotion if not a miniature form of class mobility? A chance to rise up above others, a way to prove you deserve riches others don’t, respect that others don’t. A promotion is someone who is many levels above you telling you that you deserve to get one step closer, until you may well join them at the summit of Mount Olympus.

You will do the tasks they set for you and never question their intent (“We were just following orders”). This way you evade responsibility by saying you defer to those who know better, who have the data and presentations, and who control the future with their projections.

The time comes when you have invested so much of your toil and sweat in your job that you cannot walk away. You have built such an image in front of onlookers, like a sister-in-law, that you cannot withstand ignominy. You have to be bulletproof or be glass.

And that’s what happens to Shyamal when he realises the only way to fight an act of God is by playing an act of the devil. He hesitates less than he should when concocting a scheme to create unrest among the workers to cover up a shipment delay that may cost him his promotion. He doesn’t consider waiting for his next chance, it must be now or never. The pawns can be sacrificed.

And he is so far gone down the path that he can even laugh off the thought of a worker’s death being spun for sympathy. The ladder of career advancement is often made of the bodies of the lowest rung. In fact the metonym says it all – the lowest rung. If you stop climbing you become a rung. There is no stepping off the ladder.

In the last scene of the movie, Shyamal is alone in his drawing room, cold shouldered by Tutul, and the camera pans up to slide in the ceiling fan turning above him. It looms over him like the sword of Damocles, threatening to lop off his head if the delicate balance between respectability (to himself) and reliability (to the company) ever falters.

The Labours of Labour

Where does the distinction arise between who is the worker and who is the owner? In classical Marxist terminology the differentiator is ownership, that is the ownership of the means of production. However, in modern management styles many members of upper management can view themselves as owners, though strictly speaking they aren’t.

But when one is faced with the choice to do what’s good for the company or else personally suffer the consequences, everyone can start acting like an owner. The norm of incentivising performance and linking individual reward to overall company performance (in the form of stocks, for example) means every ambitious employee becomes almost patriotic towards the abstract corporation.

In Shyamal, this mental shift has taken place so surreptitiously that the viewer is quite shocked to see how easily he can act out his plan, which involved putting the jobs, reputations, and even lives of many factory workers at risk. Workers have become collateral to his ambition, a fact not lost on the left-leaning Tutul. So far removed has Shyamal become from his own position as employee that he almost sees himself as a different species. Like a beekeeper uses smoke to knock out a colony before collecting their honey, so also can this middle management man do something similar to collect honey for himself.

His classy sophistications, his earlier sympathies for the blue-collar workers, his modernity, all of these fall by the wayside as he orchestrates the victimisation of so many. And this is especially egregious because for those people the loss of a few days’ wages could be crippling, whereas for Shyamal a few dozen square feet of living space more are all that are at stake.

After collecting the reward for his misdeeds, Shyamal returns home to find the lift up to his flat is broken and has to climb up many flights of stairs to get home. It is an indication, an omen, that things are about to get harder for him, now that he has decided to wager everything he has to keep climbing the ladder.

The film seems to tell us that there is a limit, or a glass ceiling, to how far we can get by just on talent and hard work. Beyond that if one wants to rise in a corporate world then the playbook is devilish and devious. Whether you choose to play or not is up to you.