HISTORY ALSO HAPPENS

Even though Satyajit Ray was a globally renowned filmmaker, within India his films did not reach a wide/mass audience. His films were hugely popular and celebrated within his home state of West Bengal, and among Bengali-speakers everywhere, but there weren’t many outside the state who were personally familiar with his work.

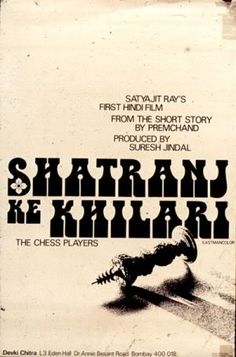

The most widely-viewed films in India have always been those made in Hindi, and it was to reach that audience that Ray would have decided to make Shatranj Ke Khiladi. Like most of his other films, here too he decided to adapt a story written by someone else – Premchand, who has a legendary status among Hindi audiences. In addition, this film also boasted the most nationally and internationally famous cast of any of his oeuvre – Amitabh Bachchan (narrator), Sanjeev Kumar, Amjad Khan, Shabana Azmi, Sayyed Jaffrey, Tom Alter, Richard Attenborough, Victor Bannerjee, Farida Jalal, and Farooq Sheikh. There was nothing niche or Bengali about this film, and no reason for a mainstream Hindi audience to ignore it (if they did that was because of their own ignorance).

War And (Chess) Piece

Shatranj Ke Khiladi is a period film, unfolding during the time when Wajid Ali Shah was being slowly displaced by the East India Company administration as the ruler of the state of Awadh. Just before the Rebellion/Revolution of 1857, it was an uneasy time before violence broke out between natives and colonisers, but a time where there were winds of change blowing.

Though clearly a historical film, it focuses less on the actual events of history, and more on the two aristocrats, Sajjad and Roshan, as they try to play innumerable games of chess. Things happen around them, behind them, even in front of them, but their attention is wholly to their games. Events domestic and political evade them, or they evade the events. Either way they fly like aeroplanes, above the weather.

But are they right or wrong to be so complacent? After all landowners can weather the storm of political change because their income and lifestyle is assured by their possessions. It is the poorer sections who will be affected, whether as bystanders during a revolution, or as participants. On the other hand, it is the ones with property who have more to lose and can be targeted specifically. Their metaphorical carcass can feed hundreds of starving peasants. So, while watching this film one has to wonder if their sense of security is justified.

Of course, our knowledge of the actual events of that period reveal that they should have been concerned with the upheaval of the times since their king was soon to be displaced. Following that, the aristocrats’ own loyalties would be challenged, their own status would be reduced, and eventually their properties could be taken away from them.

But, hindsight is 20-20 and it is hard to say what the two chess-players’ strategy should have been in that moment. After all, the tussle between the Nawab and the British was not something the public knew enough about to act upon. Even in 1857, the rebellion was struck on events not directly related to the fight for power.

What all of this goes to indicate is that history usually doesn’t unfold in pre-determinable steps or sequences. Most of us, tragically, are ignorant of the forces surrounding us and of the plots and ploys at play. Even the aristocrats know little more than the young boy who fetches them snacks. Like the husband who doesn’t know his wife and nephew are having an affair, the larger portion of society is blissfully unaware of the gambles being played with their fates.

It is an ignorant populace, one that doesn’t know the chess moves of history, that can always be content with the way things are. We may find the actions of Sajjad and Roshan infuriating, but they are no more complacent that the Nawab, or the British, who will all be taken unawares by the events that follow in the next few years.

Unlike a compact game of chess, we are not in control of our history and destiny like we want to believe. We are all pieces; some are kings, some queens, some rooks, and mostly pawns, but no individual piece controls the game. Rather each is controlled by the game. We like to think we are chess players, but actually we are all merely chess pieces.

Exercising Power, Exorcising Weakness

The Nawab of Awadh seems like a good man. He is cultured and not afraid to show his emotions. He doesn’t appear to want to rule by intimidation but by actual good governance. He revels in the prosperity of his kingdom, and this prosperity both comes from and is distributed to his subjects.

[I use qualifiers like ‘seems to’ and ‘appear to’ because, well, history is never to be taken at face value.]

But, he is also under siege by the agents of the East India Company who are determined to ease him out of his position. By that time in history (the 1850s) the traditional rulers of India had already lost much of their power to the colonisers. From the Emperors in Delhi, down to the Nawabs and Maharajas, and even the smallest governors, all were living in various stages of subjugation to the military-led trading men from Britain. In fact, the rise of the Awadh province and their Nawabs were also a consequence of the weakening of the Delhi Emperors by the British – the roller-coaster of history!

Why should it be that a Nawab of a prosperous state, whose people seem to like him, is challenged for his position by people who are neither invested in the land nor its people? The answer may be found in the old adage – nature abhors a vacuum. While this may be true for certain physical events (though more than nine-tenths of the known universe is actually vacuum) it can be taken as a certainty in the politics of power. In other words, wherever there is an absence of power, some ambitious party will rush to fill it.

One would assume that the Nawab is, by definition, powerful. He rules a huge swathe of land, commands an army, delivers judgements. That’s power. Isn’t it?

Or is it power only when it is exercised aggressively and conspicuously? The Nawab of prosperity, who has time for culture and the arts, may possibly have lost power because there is no need for it. When there is peace, there is no need for power.

It sounds strange doesn’t it? But that’s how many of the best rulers, the ones who were very good for their people, lost their position. The cut-throat interplay of power moves have always rewarded those who deal in war and aggression and decimated those who would rather make the best of what has already been achieved. On one side are unstoppable forces like Ashok and Genghis Khan, on the other side are tragic figures like Humayun and Wajid Ali. In the modern world we have many examples of the phenomenon of anti-incumbency, where even good performance can be met with rejection and loss.

Power is not like water – equally tangible as moving rivers or stagnant lakes. Power is like the air – only felt when it is in motion.

And at the end of it all, where is the common woman and man to go? Who thinks of their happiness? Those who control nearly every aspect of their lives are incentivised to constantly push the prospects of stability away and keep engaging in risky adventures with public money and lives. They nurture coteries of generals and ministers who exercise power on their behalf, which often means terrorising subjects and keeping them guessing.

If all of this feels like a digression from the film itself, please bear with me. One is just trying to move beyond the obvious.

Towards the end of the film, when Sajjad and Roshan finally discuss the arrival of British military forces into their city, signalling the imminent end of the Nawab’s rule, Roshan rues that they didn’t do anything to fight it. When Sajjad points out that there was nothing they could have really done to prevent any of it, Roshan clarifies that he doesn’t worry so much about the change in rule, as much as what it means for the continuity of their games of chess. Will they have to stop playing, at last?

And this is the tragedy of the human lust for power and the civilisation that it keeps stunting. Yes, it is true that they didn’t fight when they needed to, but why is human history an endless series of wars and strife that requires nearly every generation to fight? Why can we not lay down our weapons with assurance that somebody else will not pick them up and point them back at us? Why can these two people not enjoy a life of chess without having to sacrifice their own lives in the battlefield? Their negligence may cost them their domestic happiness, and that’s fair, but why must it cost them their very liberty and life?

That’s the agony and ecstasy of chess, or any game and sport. There is wondrous beauty in the gameplay, but in the end, winners exult in the decimation of losers, and then it starts all over again. It’s not as shocking to watch these two friends spend their entire lives just playing meaningless round-after-round of chess as it is to realise that our species has been doing exactly that for millennia. Die on the battlefield, or live to fight another day. Never just smile and walk away.