THE REMEMBRANCE OF LIVES PAST

Satyajit Ray was one of the few acclaimed directors of global film history who made so many films for children. Four were his own projects, and nearly twenty more have been made based on his stories and characters.

A lot of this would be due to the fact that his family was deeply involved in children’s stories, both as writers and publishers. Sandesh, a magazine started in 1913 by Ray’s grandfather and which is still running today, was a big part of Ray’s life as a child and later as editor. It is fair to say that stories for children had been a part of Ray’s life much longer than cinema.

When it comes to Feluda, his fictional detective, the audience connection has stayed strong even as the audience themselves grew older. Being rooted in reality (as opposed to fantasy and science-fiction series like Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne and Professor Shonku) these stories have demanded lesser suspension of disbelief from viewers and relied more on the charms of travel and puzzle-solving. Although in Sonar Kella, targeted at children, we do find the rare instance of fantasy and mystery overlapping to create a mix of imagination and intellect.

It’s The Expedition, Not The Destination

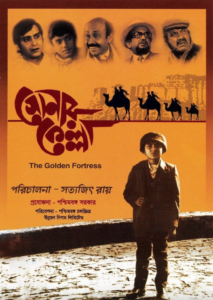

Sonar Kella was his first film for children that was also written by Ray himself. A lover of Tintin, this story gave him the chance to replicate all the aspects of the adventure stories he loved as a child. Although the presence of the great detective Feluda would indicate this is a mystery, but it’s really not. There’s no mystery to be solved, just culprits to be caught, making it more of an action-adventure tale which translates better on screen for a young audience.

The expedition, via trains, cars, and camels, was a very prevalent part of all native and colonial tales. From the days of Marco Polo it has fascinated the western world, and closer to home it has been a part of our epic mythologies and folk tales. Even the fairy tales we hear as children often have wandering exiles and travellers in magical forests. The bravery of entering uncharted territories, and the excitement of meeting new people, were what captured the imagination right up till the twentieth century. By then nearly every part of the globe had been mapped, and there wasn’t much left to explore. Of course, remote areas like the Antarctic and the moon continued to provide much excitement in recent decades.

By embarking on a long journey across India, and focussing particularly on the state of Rajasthan, the film tries to capture some of the sense of adventure that had gone missing by then. Everyone may know what a camel is, but seeing one in real life is still a thrill, especially for a child.

That’s why the journey becomes so important as a vessel for sharing a sense of wonder with young viewers (a theme that Ray expounds upon in Agantuk). The thought that one can capture scorpions, wrestle with bandits, communicate with the spirit world, makes us want to shrug off our ordinary lives full of homework and punishment, and set off like David Livingston to find the source of the Nile.

Of course, keeping the audience in mind, this is a very peculiarly Bengali form of adventure where food always takes precedence over the mission. Where else will you have multiple references to what’s eaten during the journey though it forms no part of the actual plot? This cultural quirk reaches its apex when Feluda chooses to take an extra half-hour before setting off to rescue the kid so that they can get lunch packed!

All The Women Left Behind

Something that makes me uncomfortable about Ray’s children’s films is the complete absence of significant female characters, and the near total absence of women at all. Given that in all his other films Ray had always given very powerful roles to women, the gaps in these films become quite inexplicable.

There is, of course, a tradition of downgrading women in children’s stories and detective fiction. Much of fantasy and mystery are played out as boys’ clubs – written by men, for largely male audiences. Without dragging the past into the present, I am admittedly at a bit of a loss to overlook this fact in Ray’s films.

For instance, an adventure story like Sonar Kella enacts a male fantasy of escaping domestication. Could Feluda continue in his profession if he gets married? Could Lalmohan Babu? And if Topshe ever decides to get married, can he continue accompanying his cousin on grand adventures? To be able to drop everything and travel across the world in pursuit of riches has always been seen as a masculine hobby.

This goes so far in this movie as to have the little boy Mukul being taken on a life-changing journey by his male psychiatrist and not his parents. Even his father has some role in alerting the authorities, but his mother is completely absent from the major part of the narrative even though she is glimpsed in early parts of the film. In Goopy-Bagha stories, the protagonists are grown men so they may leave their families and go off on their own. But can a six-year-old be sent off without his mother and in the company of total strangers? In pursuit of adventure one has gotten rid of the mother altogether.

One wonders if this story couldn’t have been possible with a female psychiatrist at the very least (this would have actually added more believability to the plot). Or it could have been the receptionist at the guest house, or one of the camel herders. The mind boggles at the thought.

Could it be that it would be much more unbelievable if a woman conducted herself as recklessly as some of the men (for instance, those who refuse to go to the Police for help) and that would spoil the images of daring-do? After all the escape from domesticity is an escape from what is appropriate and necessary, so to bring women along would spoil the sense of the no-holds-barred free-for-all approach.

This criticism equally applies to the rest of Ray’s children’s films Jai Baba Felunath, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, and Hirak Rajar Deshe. And it is wrong to suggest that since these are not films that are targeted at women of any age, hence it is justified do away with them. If Mahanagar can have so many male characters then why not Hirak Rajar Deshe? If Ganashatru can have a mixed cast then why not Feluda? Young girls have watched Goopy-Bagha with equal gusto, as have their mothers.

I’m sure even if it is challenging to write a story like that with significant female characters, it is a worthy challenge. After all, Ray’s heroines are known for breaking barriers, so it would have been very important to continue that tradition in these films for the eager young fans.

Child Is The father Of Man

Many who attempt to write stories for children fall into the trap of talking down to them. The most successful writers know how to address children at their own level, taking them and their views seriously and without judgement.

The film achieves this very convincingly by making the child and the detective directly connected by personality (this applies also to the character Ruku in the sequel film). Mukul is exceptionally quiet and self-assured for a boy his age. He doesn’t feel embarrassed or scared in front of strangers in the least. In fact, he appears to be capable of undertaking the entire journey on his own if he had to. Mukul doesn’t hanker for treats or demand attention. He is self-reliant and very observant, almost like a younger version of Feluda himself.

This maturity is further enhanced by the fact that the story presents Mukul as a reincarnation of a (ostensibly) centuries old person. Since the film doesn’t debunk this aspect, one can consider him as being the oldest character in the entire film.

On the contrary, the rest of the adults are all child-like or cartoonish. Their appearance is reminiscent of Tintin characters like Calculus and Rastapopoulos. One of the criminals sneers and bumbles through the film, while Lalmohan Babu grins and marvels at everything new. Even the psychiatrist, a man of medicine, behaves like a dazed dolt who prefers to hide in bushes than to alert the authorities.

None of them, other than Feluda, behave like adults would or should and this makes Mukul really distinguish himself. The child is clearly focused on the task at hand even when the adults get distracted. He doesn’t need his parents or anyone else to resolve his problems.

So the children in the audience get to see a version of themselves that doesn’t just sit around waiting for the grown-ups to do the dangerous work. Akin to the damsel-in-distress trope, the child-in-distress trope is done away with here. Instead he is actually the leader of the group, the one who everybody follows behind.

Thus, overall it is a mixed bag of good and bad representation, which nonetheless still holds sway a part of the childhoods of many Bengalis. Sometimes just uttering the name of the film can send many of us into a waking dream of a past life we had once lived.